The velocity of the last car before the gap in the traffic is always less than the velocity of the first car after the gap.

[If you think about it, you'll see that there's a logical reason for this. Not that that makes it any less annoying.]

Saturday, May 31, 2008

Painting of the Day # 1

[okay, so I've realized that if I keep waiting to write full length posts about the galleries I visited, I'm never going to get done. So I figure I'll just throw in a painting a day and do longer posts on a couple of things - Nicholas Poussin, for instance, or the Dada exhibition at the Tate Modern]

That blue! Is it Life, snatched from the woman's shoulders by a sudden wind, crackling above her like an electric ghost? Or Death, claiming her like a lover, encircling her in the flickering smoke of his arms? Is it a man she flees, or just this mortal cloak?

Slowly we take in the other details: the woman to the right, who lies in a pool of the same shimmering blue (is she an unconscious companion, or a premonition of the corpse to come?); the spilled pot; the tiny figure of Orpheus in a nearby clearing, singing his songs to an audience of wild and mythic creatures (notice the Unicorn), oblivious of the tragedy that is soon to engulf him; the city with its temples and towers already starting to vanish into the haze; and, most remarkably, the distant churn of the landscape, where the water lies still and pale while the mountains boil in great scudding waves.

Niccollo dell'Abate The Death of Eurydice

That blue! Is it Life, snatched from the woman's shoulders by a sudden wind, crackling above her like an electric ghost? Or Death, claiming her like a lover, encircling her in the flickering smoke of his arms? Is it a man she flees, or just this mortal cloak?

Slowly we take in the other details: the woman to the right, who lies in a pool of the same shimmering blue (is she an unconscious companion, or a premonition of the corpse to come?); the spilled pot; the tiny figure of Orpheus in a nearby clearing, singing his songs to an audience of wild and mythic creatures (notice the Unicorn), oblivious of the tragedy that is soon to engulf him; the city with its temples and towers already starting to vanish into the haze; and, most remarkably, the distant churn of the landscape, where the water lies still and pale while the mountains boil in great scudding waves.

Friday, May 30, 2008

Queasy Quicksands

For reasons I won't go into (much), I've decided to spend the weekend reading a random selection [1] of new 'Indian' fiction - novels and short stories from the last three or four years either published in India or by Indian writers. I keep hearing about the massive surge in new fiction coming out of India but I've read very little of it, because a) it's hard to find out here in Philly, b) between catching up on the classics and keeping up with new work by voices I already know and like I have too much to read anyway c) I always feel a little parochial reading something just because it's Indian and d) the few recent books I have read (or tried to read) have been appallingly bad.

Still, it's unfair to ignore an entire body of work based on a few hastily formed impressions, and it's possible that there are writers out there who are doing great work that I'm missing out on, so I've decided to devote the weekend to checking out the new Indian fiction scene (only cheating a little by dipping into Coetzee's tantalizing new book on the side). I think of it as a sort of penance, a sort of literary Lent, with the prospect of reading The Enchantress of Florence (which, from all accounts, is a genuine resurrection) to follow.

It's probably unfortunate, therefore, that the first book I happened to pick was this thing called Shifting Sands by Dominique Varma (Penguin, 2004) a book so excruciatingly painful it makes having your teeth extracted seem like a day at the spa. I've read some bad prose in my time but Ms. Varma's writing is so viscously awful it makes Kahlil Gibran read like Hemingway. Consider:

or this:

or this, my favorite of all, describing the anxiety of a group of prisoners in a Nazi concentration camp:

I'm not making this up. Honest. And this is a published novel - not some faux-poetic little brochure from the Rajasthan tourism department, not the blurb to some Hindustani Classical recording, not some cheesy manual from some ashram or the other - but a real novel published by Penguin whose "evocative prose" we are told "is an ode to the indestructible spirit of the human race."

And it's not like the book makes up in ideas what it lacks in style. The plot, such as it is, is a hodge-podge of storylines, each one parboiled to the point where it slips into bathos. If we're not in some commando comic version of a concentration camp, hearing about the Nazi's devious plan to turn lead into gold with the help of a crackpot old Jew obsessed with Babylon, we're sharing the oh-so-languorous sighs of the dancer Eliya, a kind of Madame Bovary meets Anarkali character, with the emotional depth of your average Mills and Boons heroine, who chooses to live (and ultimately die) in the desert fortress of Neemera for the sake of Love [2] (the object of her affection being, of course, a Rajput prince of the Siyaram suitings variety - are you gagging yet?), or we're hanging about in Paris with a trio of dubious researchers who seem to spend their time in a haze of sentiment and amorous intrigue and whose 'intellectual' speculations have all the scholarly coherence of your average undergraduate thesis. Why these stories belong together (except for the tenuous artifice of a family connection) or why it was necessary for Ms. Varma to intersperse them in the manner of an Inarritu film are questions I won't even bother to ask. Let's just say that when a novel is so bad that it leaves you physically nauseous you have to wonder what the editors were thinking. If all the other books I've picked up are even half as bad as this one it's going to be a long, long weekend.

Meanwhile, in other news, don't you just love Anthony Lane. Can you imagine a more damning comment on a film than comparing it unfavorably to Funny Face?

Notes

[1] Well, technically a random selection from what new Indian writing has made its way to the UPenn library - but if anything, I would think this biases my sample towards a more favorable view of what's being published.

[2] Ms. Varma writes:

Still, it's unfair to ignore an entire body of work based on a few hastily formed impressions, and it's possible that there are writers out there who are doing great work that I'm missing out on, so I've decided to devote the weekend to checking out the new Indian fiction scene (only cheating a little by dipping into Coetzee's tantalizing new book on the side). I think of it as a sort of penance, a sort of literary Lent, with the prospect of reading The Enchantress of Florence (which, from all accounts, is a genuine resurrection) to follow.

It's probably unfortunate, therefore, that the first book I happened to pick was this thing called Shifting Sands by Dominique Varma (Penguin, 2004) a book so excruciatingly painful it makes having your teeth extracted seem like a day at the spa. I've read some bad prose in my time but Ms. Varma's writing is so viscously awful it makes Kahlil Gibran read like Hemingway. Consider:

"The tranquil camels glide between thorny bushes unmindful of their prickly barbs, leaving in the sand the imprint of their undulating footsteps. A greater peace in the world than this landscape of yellow dust glowing with the iridiscent orange of the receding dusk is impossible to find. The desert acquires a wealth of colours and thick forests of clouds cast their tormented shadows over the wavy dunes."

or this:

"Leaning over the parapet, Eliya contemplated the cascading terraces descending towards the dunes pierced with trees falling over the horizon. The bitter tea turned lukewarm on the guardrail, and her senses, sharpened by the ardent fever of the sands, wrenched languorously under the spell that had held her in its thrall right from the very first time she'd felt its poignant harmony."

or this, my favorite of all, describing the anxiety of a group of prisoners in a Nazi concentration camp:

"they were all going berserk, ready to give up this derisory thread of life which sometimes seemed so precious that they would have gone down on their knees to beg it be left unbroken, to save even a tiny fragment of this fabric which was unravelling before their eyes, like a carpet whose framework was being eaten by moths. And the invisible insects nibbling at the woollen threads masticated with quiet equanimity, abandoning one edge of the carpet to attack, from inside, a more solid thread that took their fancy."

I'm not making this up. Honest. And this is a published novel - not some faux-poetic little brochure from the Rajasthan tourism department, not the blurb to some Hindustani Classical recording, not some cheesy manual from some ashram or the other - but a real novel published by Penguin whose "evocative prose" we are told "is an ode to the indestructible spirit of the human race."

And it's not like the book makes up in ideas what it lacks in style. The plot, such as it is, is a hodge-podge of storylines, each one parboiled to the point where it slips into bathos. If we're not in some commando comic version of a concentration camp, hearing about the Nazi's devious plan to turn lead into gold with the help of a crackpot old Jew obsessed with Babylon, we're sharing the oh-so-languorous sighs of the dancer Eliya, a kind of Madame Bovary meets Anarkali character, with the emotional depth of your average Mills and Boons heroine, who chooses to live (and ultimately die) in the desert fortress of Neemera for the sake of Love [2] (the object of her affection being, of course, a Rajput prince of the Siyaram suitings variety - are you gagging yet?), or we're hanging about in Paris with a trio of dubious researchers who seem to spend their time in a haze of sentiment and amorous intrigue and whose 'intellectual' speculations have all the scholarly coherence of your average undergraduate thesis. Why these stories belong together (except for the tenuous artifice of a family connection) or why it was necessary for Ms. Varma to intersperse them in the manner of an Inarritu film are questions I won't even bother to ask. Let's just say that when a novel is so bad that it leaves you physically nauseous you have to wonder what the editors were thinking. If all the other books I've picked up are even half as bad as this one it's going to be a long, long weekend.

Meanwhile, in other news, don't you just love Anthony Lane. Can you imagine a more damning comment on a film than comparing it unfavorably to Funny Face?

Notes

[1] Well, technically a random selection from what new Indian writing has made its way to the UPenn library - but if anything, I would think this biases my sample towards a more favorable view of what's being published.

[2] Ms. Varma writes:

"Should we not vow never to hate someone we have once loved, even if he becomes hateful? Out of respect for that beautiful love which was once our reason for living, and which so quickly becomes our reason for dying. Dying for love is perhaps the only desirable death, because it snatches us from the banality of dying from old age, accident, sickness. At least we know why we are dying. Because we had believed we had seen the abysses of heaven open up before us."

Thursday, May 29, 2008

The National Gallery - 1250 to 1500

There's nothing quite like the Old Masters, is there? The sublime domesticity of the Arnolfinis, for instance, or Lippi's glorious Annunciation (above), its two figures - man and woman, angel and mortal - balanced so perfectly that the very burden of the news they share is rendered weightless, the fulcrum of God's hand proves irrelevant, and these two people, conspirators in the divine, seem bathed in the sheer resplendence of the moment: the shimmer of wings on his side, the glow of the chair-draping mantle on hers.

But there are other, less anticipated delights to be found in this section of the National Gallery. Delights such as the paintings of Cosimo Tura, with their lifelike faces so at odds with the rest that I am reminded, for some strange reason, of Klimt; or the striking, almost X-ray like visions of Andrea Mantegna (such as Samson and Delilah - above - which looks at though it had been painted out of ash and magma) which seem to invert the light even as they blaze with it; or Sassetta's curiously feminine depiction of St. Francis as a chastely naked young man being embraced by the Church as his father rages at being renounced; or Cosimo's frenzied, writhing battle scene between the Centaurs and the Lapiths, with its Bosch-like landscape and its contrast between a huddle of panicked forms and the poignant image of a young woman mourning her dead lover, all enclosed in parantheses of violence. Not to mention Durer's startlingly lifelike portrait of his father (below) or his almost abstract expressionist depiction of the Last Judgement on the reverse side of a painting of Saint Jerome.

But there are other, less anticipated delights to be found in this section of the National Gallery. Delights such as the paintings of Cosimo Tura, with their lifelike faces so at odds with the rest that I am reminded, for some strange reason, of Klimt; or the striking, almost X-ray like visions of Andrea Mantegna (such as Samson and Delilah - above - which looks at though it had been painted out of ash and magma) which seem to invert the light even as they blaze with it; or Sassetta's curiously feminine depiction of St. Francis as a chastely naked young man being embraced by the Church as his father rages at being renounced; or Cosimo's frenzied, writhing battle scene between the Centaurs and the Lapiths, with its Bosch-like landscape and its contrast between a huddle of panicked forms and the poignant image of a young woman mourning her dead lover, all enclosed in parantheses of violence. Not to mention Durer's startlingly lifelike portrait of his father (below) or his almost abstract expressionist depiction of the Last Judgement on the reverse side of a painting of Saint Jerome.

But the real star of this section of the Gallery, for me, was indisputably Sandro Botticelli. The charming and forthright portrait of a delectable young man in a red beretta staring straight out at the viewer. The dramatic Venus and Mars, where the seriousness of the grown-ups - his exhaustion, her patient watchfulness - is set against the gaiety of the young satyrs (their casual games with the dread instruments of war both a triumph of innocence and a perversion), so that this meeting of two deities is transformed into a strangely domestic scene: the young husband returned from war wanting only to rest and forget, the wife a little awkward, watching him with a mix of anxiety and expectation, so completely absorbed in his presence that she barely notices the children running riot. And the glorious Adoration of the Kings (below), its circular shape drawing the eye inexorably to the Virgin and Child who are in every way the center of the scene, yet the painting itself almost triangular, a pyramid of forms rising in strict heirarchy from the mingled crowd of men and horses at the base, to the select circle of kings paying their homage to the infant Christ and further to the pointed wooden roof that hovers above the scene like a protective spirit, the plain wooden structure itself enclosed in an arch of the ruined temple (again the triangle enclosed within the semi-circle) that symbolizes the end of all things Roman even as it lends the scene a greater majesty, and is transformed, by the imagination, into a covenant of purity, an emblem of new entrances, and the ceiling of an impromptu stage. But most of all that unforgettable peacock, dainty as a courtier, regally surveying the scene, while behind and beneath him the horses neigh and the trumpets blare, proclaiming the arrival of the greatest King of all.

Wednesday, May 28, 2008

Kicking and Screaming

As you've probably heard by now, my trip to London wasn't all about museums and art galleries, I also managed to take in a football match [1], mostly because S., who I was staying with, is a football fan and it was either watch the match with her or spend the next two days sleeping in the Tube station. S.'s original plan was that we would go to a pub and watch the match from there, thus making it a quintessentially British experience, but she thought the better of that after I pointed out to her that a) I had no medical insurance in the UK b) as my host she was honor bound to defend me against any and all hooligans trying to batter me to pulp and c) my comments during football matches tend to be along the lines of "Oooh! he's cute!". So instead we settled for watching it from the privacy of her home, with, in deference to her Amriki visitor, a ready supply of beer and chips laid on for the event.

Here's roughly how it went (times are approximate):

7.45 pm: Turn on television. Players coming out on field. Get told by S. that 'we' are going to be cheering for Chelsea. Look appropriately enthusiastic. Ask for beer.

7.50 pm: Match begins. Ask for second beer.

7.55 pm: Ask for third beer.

8.02 pm: Give loud cheer for Chelsea and ask for fourth beer. Wonder why you ever thought football was dull.

8.10 pm: Chelsea scores!! Cheer loudly.

8.11 pm: Get glared at by S. Discover that Chelsea is the team in BLUE. Realize you've been cheering for Man U all along. Ah well.

8.15 pm: D. (who's joining us for dinner) arrives. Discover she doesn't much care for football either. Convince S. to mute volume on TV set so we can have conversation. Point out that the commentators are a bunch of idiots anyway and an aficionado like her should form her own opinion by watching the match with the sound turned off. Reward S. for seeing the logic of this by getting fifth beer yourself.

8.22 pm: Glance at TV while reaching for chips. Notice score is now 1-1. Chelsea must have scored at some point. Mention this casually to S (who is busy on the phone ordering food - at least the girl has her priorities straight) and go back to conversation with D.

8.32 pm: Glance away from D for a moment and give out loud bellow! S. has just kicked over the bowl of chips! Foul! foul!

8.42 pm: Glance at TV to make sure score is still 1-1.

8.55 pm: Decide to make effort to watch match. After all, it can't be that bad.

8.57 pm: Biryani that S. has ordered arrives. Forget match. Focus on food.

9.05 pm: Glance at TV to make sure score is still 1-1. Make polite comment about match to S before asking her to pass the raita.

9.20 pm: Glance at TV to make sure score is still 1-1.

9.25 pm: Glance at TV and notice that it's raining in....wherever the match is. Watch game with renewed interest, having realized that the only thing better than a bunch of cute guys running about in shorts acting all butch is a bunch of cute guys running around in soaking wet shorts acting all butch.

9.35 pm: Players seem to have given up on playing football and are standing around playing a really violent game of charades. One guy is waving something red. Ask S. if this is a good thing. Withdraw question hastily after you see look in her eyes.

9.45 pm: Penalty shoot-outs! Yaay! Wonder why they bother with the hour and a half of people running around and elbowing each other when this part is so much more fun.

9.50 pm: Watch penalty shoot-outs thinking fondly of your days being goalkeeper during PE period back in school [2]. Wish all those doubting Amits who argued that you weren't doing it properly were here now so you could show them that diving gracefully to the left while the ball is flying right is, in fact, a perfectly legit football move.

9.51 pm: Laugh wildly at guy taking penalty kick who manages to miss the goal entirely. Stop in mid-cackle because the guy is from Chelsea and S. is now looking positively murderous. Console yourself with knowledge that you were going to sleep on the couch anyway, so you have nothing to lose.

9.55 pm: The match is over! Someone has won! The guys with the goalkeeper in green [3]! Yaay! Yaay? Oops, Man U won. Look suitably crestfallen. Bitch about the unfairness of the umpires (what's that? they're called referees - ya, well, same thing) and the stupidity of having penalty shoot outs.

9.57 pm: Have awwww moment watching cute guy you've had your eye on through the match dissolving into tears. Restrain yourself from saying "Come to Papa!" out loud.

10.00 pm: End of match. Console S. by pointing about that it's just a silly national tournament - it's not like it's the World Cup or something.

10.01 pm: Discover that it's actually an all-Europe tournament and is pretty much the biggest cup these clubs can compete for. Oops!

10.02 pm: Display sensitivity and tact by refusing to talk about the match and / or football anymore. Change subject to talking about art galleries and museums. Make mental pledge not to talk about football at all for the rest of your trip. All in the interests of taking S.'s mind off it, of course.

Notes

[1] I mean, of course, real football. Not the blink-and-you-missed-it, guys-wearing-the-kind-of-shoulder-pads-that-went-out-in-the-80s variety they play out here in the barbaric West.

[2] See here.

[3] Seriously, why is it that goalkeepers in football never seem to have uniforms that go with what the rest of their team is wearing. Is there a union of football uniform makers who will only work in multiples of 10 or something? And how hard could it be to find something to wear that at least vaguely approximated your team's colors. Can you imagine if the same thing happened in cricket. There would be the Indian team, arrayed all around the field in their trademark cheap distemper blue - all except for the Wicketkeeper who was wearing a shiny magenta number with a pearl choker under his helmet.

Here's roughly how it went (times are approximate):

7.45 pm: Turn on television. Players coming out on field. Get told by S. that 'we' are going to be cheering for Chelsea. Look appropriately enthusiastic. Ask for beer.

7.50 pm: Match begins. Ask for second beer.

7.55 pm: Ask for third beer.

8.02 pm: Give loud cheer for Chelsea and ask for fourth beer. Wonder why you ever thought football was dull.

8.10 pm: Chelsea scores!! Cheer loudly.

8.11 pm: Get glared at by S. Discover that Chelsea is the team in BLUE. Realize you've been cheering for Man U all along. Ah well.

8.15 pm: D. (who's joining us for dinner) arrives. Discover she doesn't much care for football either. Convince S. to mute volume on TV set so we can have conversation. Point out that the commentators are a bunch of idiots anyway and an aficionado like her should form her own opinion by watching the match with the sound turned off. Reward S. for seeing the logic of this by getting fifth beer yourself.

8.22 pm: Glance at TV while reaching for chips. Notice score is now 1-1. Chelsea must have scored at some point. Mention this casually to S (who is busy on the phone ordering food - at least the girl has her priorities straight) and go back to conversation with D.

8.32 pm: Glance away from D for a moment and give out loud bellow! S. has just kicked over the bowl of chips! Foul! foul!

8.42 pm: Glance at TV to make sure score is still 1-1.

8.55 pm: Decide to make effort to watch match. After all, it can't be that bad.

8.57 pm: Biryani that S. has ordered arrives. Forget match. Focus on food.

9.05 pm: Glance at TV to make sure score is still 1-1. Make polite comment about match to S before asking her to pass the raita.

9.20 pm: Glance at TV to make sure score is still 1-1.

9.25 pm: Glance at TV and notice that it's raining in....wherever the match is. Watch game with renewed interest, having realized that the only thing better than a bunch of cute guys running about in shorts acting all butch is a bunch of cute guys running around in soaking wet shorts acting all butch.

9.35 pm: Players seem to have given up on playing football and are standing around playing a really violent game of charades. One guy is waving something red. Ask S. if this is a good thing. Withdraw question hastily after you see look in her eyes.

9.45 pm: Penalty shoot-outs! Yaay! Wonder why they bother with the hour and a half of people running around and elbowing each other when this part is so much more fun.

9.50 pm: Watch penalty shoot-outs thinking fondly of your days being goalkeeper during PE period back in school [2]. Wish all those doubting Amits who argued that you weren't doing it properly were here now so you could show them that diving gracefully to the left while the ball is flying right is, in fact, a perfectly legit football move.

9.51 pm: Laugh wildly at guy taking penalty kick who manages to miss the goal entirely. Stop in mid-cackle because the guy is from Chelsea and S. is now looking positively murderous. Console yourself with knowledge that you were going to sleep on the couch anyway, so you have nothing to lose.

9.55 pm: The match is over! Someone has won! The guys with the goalkeeper in green [3]! Yaay! Yaay? Oops, Man U won. Look suitably crestfallen. Bitch about the unfairness of the umpires (what's that? they're called referees - ya, well, same thing) and the stupidity of having penalty shoot outs.

9.57 pm: Have awwww moment watching cute guy you've had your eye on through the match dissolving into tears. Restrain yourself from saying "Come to Papa!" out loud.

10.00 pm: End of match. Console S. by pointing about that it's just a silly national tournament - it's not like it's the World Cup or something.

10.01 pm: Discover that it's actually an all-Europe tournament and is pretty much the biggest cup these clubs can compete for. Oops!

10.02 pm: Display sensitivity and tact by refusing to talk about the match and / or football anymore. Change subject to talking about art galleries and museums. Make mental pledge not to talk about football at all for the rest of your trip. All in the interests of taking S.'s mind off it, of course.

Notes

[1] I mean, of course, real football. Not the blink-and-you-missed-it, guys-wearing-the-kind-of-shoulder-pads-that-went-out-in-the-80s variety they play out here in the barbaric West.

[2] See here.

[3] Seriously, why is it that goalkeepers in football never seem to have uniforms that go with what the rest of their team is wearing. Is there a union of football uniform makers who will only work in multiples of 10 or something? And how hard could it be to find something to wear that at least vaguely approximated your team's colors. Can you imagine if the same thing happened in cricket. There would be the Indian team, arrayed all around the field in their trademark cheap distemper blue - all except for the Wicketkeeper who was wearing a shiny magenta number with a pearl choker under his helmet.

Tuesday, May 27, 2008

Stray Thoughts on the British Museum

Wandering through the British Museum is a bit like walking through the intestines of a defunct monster - some gluttonous Kraken or ferocious T-Rex - and seeing the half-digested remains of the creatures it has swallowed. I suppose it's only fitting that the British Museum should end up as a sort of general storehouse for dead empires. Still I kept feeling like I should ask where the shield of Vercingetorix was.

***

If the British Museum has a presiding deity, it is John Keats. Oh, Cavafy puts in an appearance, and Homer, and it's hard to see the Assyrian friezes depicting the seige of Lachish without thinking of Byron, or gaze on the colossal head of a Pharoah without remembering Shelley, but it's Keats who comes most to mind as one wanders through the Greek galleries [1]. It's not just the thrill of finally seeing the long-promised Elgin Marbles, it's the lines from Ode on a Grecian Urn, which keep repeating and repeating in your head as you roam the exhibits.

Because it's all there, isn't it? The green altar with its mysterious priest, the loth maidens, the bold lovers, the little town by river or sea-shore. To wander through these galleries is to hear, at last, Keats' unheard melodies - the swelling adagio of grief as the warriors carry the body of their comrade off the battlefield, the furious allegro of the leaping amazon,

the swelling adagio of grief as the warriors carry the body of their comrade off the battlefield, the furious allegro of the leaping amazon,  the gavotte of pride in a young boy's heart as he rides in his first procession and the mellow andante in the heart of the bystanders as they admire the boy's beauty - all the fierce and solemn music of an unforgettable age. This is poetry - these clean yet fluid lines depicting a reality that transcends itself, this blending of energy and grace, this balance of the immediate and the timeless. There is something almost cinematic about the way these sculptures move us; something about the breathtaking realism of these depictions their individuality, their attention to detail. To see a centaur twisting in pain in one of these friezes is to find yourself suddenly on the plain of war, hearing the screams of the dying and wounded, feeling the adrenalin of battle pulsing through your blood.

the gavotte of pride in a young boy's heart as he rides in his first procession and the mellow andante in the heart of the bystanders as they admire the boy's beauty - all the fierce and solemn music of an unforgettable age. This is poetry - these clean yet fluid lines depicting a reality that transcends itself, this blending of energy and grace, this balance of the immediate and the timeless. There is something almost cinematic about the way these sculptures move us; something about the breathtaking realism of these depictions their individuality, their attention to detail. To see a centaur twisting in pain in one of these friezes is to find yourself suddenly on the plain of war, hearing the screams of the dying and wounded, feeling the adrenalin of battle pulsing through your blood.

This is poetry, I said, but it is also history. For to gaze upon these sculptures is also to see the slow erosion of memory, to see how time erases us, how little by little each treasured detail is lost, until what was nameless to start with becomes faceless, deformed, and what is left is only a museum's worth of abstract gestures - the raising, in defiance, of a broken-off arm, or an eloquent glance backwards, emerging from a wasteland of scuffed rock.

[1] It should come as no surprise to readers of this blog that I spent most of my time at the British Museum in the Greek and Roman sections. And while we're on the subject, will someone please explain to me why the public imagination is so taken with the Egyptians? The crowds in the Egyptian gallery outnumbered those in every other part of the Museum three to one, so that walking through the Egyptian section meant you were elbowing your way through a pressed rank of tourists, or dodging your way through a crossfire of photo ops. Is it the Mummy movies? Is it Tintin? Seriously, what's the fascination?

***

If the British Museum has a presiding deity, it is John Keats. Oh, Cavafy puts in an appearance, and Homer, and it's hard to see the Assyrian friezes depicting the seige of Lachish without thinking of Byron, or gaze on the colossal head of a Pharoah without remembering Shelley, but it's Keats who comes most to mind as one wanders through the Greek galleries [1]. It's not just the thrill of finally seeing the long-promised Elgin Marbles, it's the lines from Ode on a Grecian Urn, which keep repeating and repeating in your head as you roam the exhibits.

Because it's all there, isn't it? The green altar with its mysterious priest, the loth maidens, the bold lovers, the little town by river or sea-shore. To wander through these galleries is to hear, at last, Keats' unheard melodies -

the swelling adagio of grief as the warriors carry the body of their comrade off the battlefield, the furious allegro of the leaping amazon,

the swelling adagio of grief as the warriors carry the body of their comrade off the battlefield, the furious allegro of the leaping amazon,  the gavotte of pride in a young boy's heart as he rides in his first procession and the mellow andante in the heart of the bystanders as they admire the boy's beauty - all the fierce and solemn music of an unforgettable age. This is poetry - these clean yet fluid lines depicting a reality that transcends itself, this blending of energy and grace, this balance of the immediate and the timeless. There is something almost cinematic about the way these sculptures move us; something about the breathtaking realism of these depictions their individuality, their attention to detail. To see a centaur twisting in pain in one of these friezes is to find yourself suddenly on the plain of war, hearing the screams of the dying and wounded, feeling the adrenalin of battle pulsing through your blood.

the gavotte of pride in a young boy's heart as he rides in his first procession and the mellow andante in the heart of the bystanders as they admire the boy's beauty - all the fierce and solemn music of an unforgettable age. This is poetry - these clean yet fluid lines depicting a reality that transcends itself, this blending of energy and grace, this balance of the immediate and the timeless. There is something almost cinematic about the way these sculptures move us; something about the breathtaking realism of these depictions their individuality, their attention to detail. To see a centaur twisting in pain in one of these friezes is to find yourself suddenly on the plain of war, hearing the screams of the dying and wounded, feeling the adrenalin of battle pulsing through your blood.

This is poetry, I said, but it is also history. For to gaze upon these sculptures is also to see the slow erosion of memory, to see how time erases us, how little by little each treasured detail is lost, until what was nameless to start with becomes faceless, deformed, and what is left is only a museum's worth of abstract gestures - the raising, in defiance, of a broken-off arm, or an eloquent glance backwards, emerging from a wasteland of scuffed rock.

[1] It should come as no surprise to readers of this blog that I spent most of my time at the British Museum in the Greek and Roman sections. And while we're on the subject, will someone please explain to me why the public imagination is so taken with the Egyptians? The crowds in the Egyptian gallery outnumbered those in every other part of the Museum three to one, so that walking through the Egyptian section meant you were elbowing your way through a pressed rank of tourists, or dodging your way through a crossfire of photo ops. Is it the Mummy movies? Is it Tintin? Seriously, what's the fascination?

Sunday, May 25, 2008

Clips

Emptying my backpack today, I find a handful of used paper clips at the bottom.

Evidence of all that has come undone through the years, emblems of all that has slipped away.

***

The hunger of binder clips frightens me. These objects that are pure bite, pure jaw. I am appalled by the tenacity with which they hold on to their prey, and by their capacity for cannibalism, the way they lock together, mouths joined in a feral compact that is more combat than kiss.

At other times though, I am touched by how gently they hold the manuscripts I entrust to them; the way they take these delicate reams of paper by the scruff of their necks, like a mother dangling her cubs in her mouth, and deliver them to me, when the time comes, entirely unharmed.

Yet they are not all docility, not all obedience. For I have felt their resistance straining against me when I lever open their jaws and try to fit my papers between them, like a petty dictator stuffing the mouth of his subjects with his own opinions. At times like these they are like obstinate children, who will not eat what is good for them - they must be co-opted, coerced - and often, in this process, a stray sheet of paper will spill over and the whole offering will have to be withdrawn, retrieved, offered again.

It says a lot for my own fragility as a writer that I experience their reluctance to take my words into their mouth, mechanical and unthinking as it undoubtably is, as a kind of rejection, so that if the clip will not close over the manuscript after, say, the third try, I will often conclude that I must revise the manuscript, when it would be better perhaps to search for a more expansive audience, a larger size of clips.

Evidence of all that has come undone through the years, emblems of all that has slipped away.

***

The hunger of binder clips frightens me. These objects that are pure bite, pure jaw. I am appalled by the tenacity with which they hold on to their prey, and by their capacity for cannibalism, the way they lock together, mouths joined in a feral compact that is more combat than kiss.

At other times though, I am touched by how gently they hold the manuscripts I entrust to them; the way they take these delicate reams of paper by the scruff of their necks, like a mother dangling her cubs in her mouth, and deliver them to me, when the time comes, entirely unharmed.

Yet they are not all docility, not all obedience. For I have felt their resistance straining against me when I lever open their jaws and try to fit my papers between them, like a petty dictator stuffing the mouth of his subjects with his own opinions. At times like these they are like obstinate children, who will not eat what is good for them - they must be co-opted, coerced - and often, in this process, a stray sheet of paper will spill over and the whole offering will have to be withdrawn, retrieved, offered again.

It says a lot for my own fragility as a writer that I experience their reluctance to take my words into their mouth, mechanical and unthinking as it undoubtably is, as a kind of rejection, so that if the clip will not close over the manuscript after, say, the third try, I will often conclude that I must revise the manuscript, when it would be better perhaps to search for a more expansive audience, a larger size of clips.

Saturday, May 24, 2008

Martin Lewis

My apologies for the long hiatus, but I was in London for a bit - first attending a conference and then mooching about the city's museums and art galleries. At any rate, I'm back now, and come loaded with so many impressions and images all swirling about in my head that for the foreseeable future this blog is going to be about art, art and more art.

And what better place to start than with Martin Lewis - an artist I'd never heard of before, but discovered in a special exhibition at, of all places, the British Museum [1]. The exhibition places Lewis next to Hopper, and it is a place he richly deserves. Lewis' prints have the timeless quality of black and white photographs - breathtakingly realistic in detail, they deploy a spectrum of shades to create a vision of New York that is as murky as it is translucent, that both celebrates the contemporary and transcends it to suggest something darker, more human. This is the soul of the city captured not in light, but in shadow; this is the language of noir - an alchemy by which the ephemeral is transformed into the achingly beautiful.

In Spring Night, Greenwich Village (above) for instance, Lewis captures both the hustle of the city and the plodding stillness at its heart. The street is crowded with shadowy figures - a couple kisses in a doorway, children and pedestrians hurry past. Yet even as we absorb this everyday traffic our eyes are drawn inexorably to a figure in the center who stands silhouetted against the light - a girl who stands before a lighted storefront, watching the cobbler inside as he bends over his work. The child's stationary pose, her turned back (most of the other figures are seen sideways), the light through the shop window - all these serve as a visual break in the rhythm of the print, focusing attention on the girl, making us pause and take notice even as she herself is doing. And in that moment of contemplation an everyday street scene is turned into a minor epiphany, an image of youth confronting age, of spring confronting night, a break in the daily round of existence as the mind stops to contemplate some harsh reality, or to watch, fascinated, a sight it has passed by many times but never really seen before. There is both wonder and horror here, but more than that there is a sense of being confronted with something preternaturally true that must be made sense of - an image every bit as glowing and brilliant as the window the girl stands facing, and one that casts a shadow in the mind as long as the one falling behind her.

A similar feeling of confrontation informs Passing Freight, Danbury (below) where the dynamic, invading presence of the train is counterpointed against the two umbrella-carrying figures who stand waiting for it to pass. Here again we have an external reality that the central figures in the image are forced to confront, yet it is the presence of these two women, as well as the sleepy looking house towering above them, that anchors the train in a specific landscape, gives it both meaning and a sense of proportion. Here is a meeting of shadowy vectors, a balance of force and stasis temporarily achieved, the juxtaposition of the train and the house perfectly paralleled by the lines of electricity running horizontal along the top of the painting and the pillar rising vertically to meet them. But notice also the precision with which Lewis renders the light effects here - the ray of the locomotive's headlamp radiating out into the unknown, the glint of light on the metal of the train, and the sheen of the road after the recent rainfall (remember the umbrellas) so that the sidewall of the house is reflected on the pavement.

My favorite Lewis print of all though is Saturday's Children (below) with its vision of a weary humanity. This time the confrontation is two fold - on the one hand the everyday storefronts on the left seem at odds with the turret like buildings rising on the right, their mythic quality enhanced by the sunbeams that come streaming through them, bathing the scene in light. But there is a second confrontation here, one between the viewer and the approaching crowd. One woman, in particular, stands out - she is two steps ahead of the others, alone, facing straight at us, and almost vertically above her rises a lamppost shaped like a weighing scale - so that this unremarkable figure, this face in a crowd, is transformed into a kind of nemesis, and we are forced to confront, in the semblance of an ordinary passerby, the faceless drudgery of work, the monotony of existence, and the endless stream of days that approach us and go by unnoticed, unremarked.

[1] What an exhibition of Twentieth Century American Prints was doing in the British Museum I don't know. Any more than I know why the gallery showing the exhibition also included a 'cartoon' by Michelangelo.

And what better place to start than with Martin Lewis - an artist I'd never heard of before, but discovered in a special exhibition at, of all places, the British Museum [1]. The exhibition places Lewis next to Hopper, and it is a place he richly deserves. Lewis' prints have the timeless quality of black and white photographs - breathtakingly realistic in detail, they deploy a spectrum of shades to create a vision of New York that is as murky as it is translucent, that both celebrates the contemporary and transcends it to suggest something darker, more human. This is the soul of the city captured not in light, but in shadow; this is the language of noir - an alchemy by which the ephemeral is transformed into the achingly beautiful.

In Spring Night, Greenwich Village (above) for instance, Lewis captures both the hustle of the city and the plodding stillness at its heart. The street is crowded with shadowy figures - a couple kisses in a doorway, children and pedestrians hurry past. Yet even as we absorb this everyday traffic our eyes are drawn inexorably to a figure in the center who stands silhouetted against the light - a girl who stands before a lighted storefront, watching the cobbler inside as he bends over his work. The child's stationary pose, her turned back (most of the other figures are seen sideways), the light through the shop window - all these serve as a visual break in the rhythm of the print, focusing attention on the girl, making us pause and take notice even as she herself is doing. And in that moment of contemplation an everyday street scene is turned into a minor epiphany, an image of youth confronting age, of spring confronting night, a break in the daily round of existence as the mind stops to contemplate some harsh reality, or to watch, fascinated, a sight it has passed by many times but never really seen before. There is both wonder and horror here, but more than that there is a sense of being confronted with something preternaturally true that must be made sense of - an image every bit as glowing and brilliant as the window the girl stands facing, and one that casts a shadow in the mind as long as the one falling behind her.

A similar feeling of confrontation informs Passing Freight, Danbury (below) where the dynamic, invading presence of the train is counterpointed against the two umbrella-carrying figures who stand waiting for it to pass. Here again we have an external reality that the central figures in the image are forced to confront, yet it is the presence of these two women, as well as the sleepy looking house towering above them, that anchors the train in a specific landscape, gives it both meaning and a sense of proportion. Here is a meeting of shadowy vectors, a balance of force and stasis temporarily achieved, the juxtaposition of the train and the house perfectly paralleled by the lines of electricity running horizontal along the top of the painting and the pillar rising vertically to meet them. But notice also the precision with which Lewis renders the light effects here - the ray of the locomotive's headlamp radiating out into the unknown, the glint of light on the metal of the train, and the sheen of the road after the recent rainfall (remember the umbrellas) so that the sidewall of the house is reflected on the pavement.

My favorite Lewis print of all though is Saturday's Children (below) with its vision of a weary humanity. This time the confrontation is two fold - on the one hand the everyday storefronts on the left seem at odds with the turret like buildings rising on the right, their mythic quality enhanced by the sunbeams that come streaming through them, bathing the scene in light. But there is a second confrontation here, one between the viewer and the approaching crowd. One woman, in particular, stands out - she is two steps ahead of the others, alone, facing straight at us, and almost vertically above her rises a lamppost shaped like a weighing scale - so that this unremarkable figure, this face in a crowd, is transformed into a kind of nemesis, and we are forced to confront, in the semblance of an ordinary passerby, the faceless drudgery of work, the monotony of existence, and the endless stream of days that approach us and go by unnoticed, unremarked.

The exhibition has many other delights to offer. There's Hopper of course - with the haunting Night on the El Train and the starkly scintillating Evening Wind. There's Bellows with his Stag at Sharkey's in all its sweaty, muscular glory and Business Men's Bath where the clean, proud lines of youth jostle side by side with the bloated self-importance of middle-age. There's Thomas Hart Benton's The Race, where a horse's streaming mane is echoed both in the pure curve of its reflection in the water as well as the spume of smoke the racing train leaves behind it. There's John Marin's delightful Brooklyn Bridge Swaying where a few deft pencil strokes transform the solidest of structures into a jazz like visual improvisation that you can almost see swinging in front of you.

Benton's The Race, where a horse's streaming mane is echoed both in the pure curve of its reflection in the water as well as the spume of smoke the racing train leaves behind it. There's John Marin's delightful Brooklyn Bridge Swaying where a few deft pencil strokes transform the solidest of structures into a jazz like visual improvisation that you can almost see swinging in front of you.  The horrors of war find expression through Benton Spruance's Riders of the Apocalpyse (left) with its faux-cubist image of planes flying through the searchlight torn sky, and Tranquility (right) which shows the painter at work wearing a gas mask while air raids carry on outside. And just in case you were getting sick of all this black and white there's always the apocalyptic Europa (below). All in all, an exhibition definitely worth the visit.

The horrors of war find expression through Benton Spruance's Riders of the Apocalpyse (left) with its faux-cubist image of planes flying through the searchlight torn sky, and Tranquility (right) which shows the painter at work wearing a gas mask while air raids carry on outside. And just in case you were getting sick of all this black and white there's always the apocalyptic Europa (below). All in all, an exhibition definitely worth the visit.

Benton's The Race, where a horse's streaming mane is echoed both in the pure curve of its reflection in the water as well as the spume of smoke the racing train leaves behind it. There's John Marin's delightful Brooklyn Bridge Swaying where a few deft pencil strokes transform the solidest of structures into a jazz like visual improvisation that you can almost see swinging in front of you.

Benton's The Race, where a horse's streaming mane is echoed both in the pure curve of its reflection in the water as well as the spume of smoke the racing train leaves behind it. There's John Marin's delightful Brooklyn Bridge Swaying where a few deft pencil strokes transform the solidest of structures into a jazz like visual improvisation that you can almost see swinging in front of you.  The horrors of war find expression through Benton Spruance's Riders of the Apocalpyse (left) with its faux-cubist image of planes flying through the searchlight torn sky, and Tranquility (right) which shows the painter at work wearing a gas mask while air raids carry on outside. And just in case you were getting sick of all this black and white there's always the apocalyptic Europa (below). All in all, an exhibition definitely worth the visit.

The horrors of war find expression through Benton Spruance's Riders of the Apocalpyse (left) with its faux-cubist image of planes flying through the searchlight torn sky, and Tranquility (right) which shows the painter at work wearing a gas mask while air raids carry on outside. And just in case you were getting sick of all this black and white there's always the apocalyptic Europa (below). All in all, an exhibition definitely worth the visit.

[1] What an exhibition of Twentieth Century American Prints was doing in the British Museum I don't know. Any more than I know why the gallery showing the exhibition also included a 'cartoon' by Michelangelo.

Sunday, May 11, 2008

Frida

Wandering through the Philadelphia Art Museum's exhibition of the paintings of Frida Kahlo last Thursday, I couldn't help think of the similarities between Kahlo's work and Courbet's. Both are artists deeply invested in their self-image, to the point where their work, were it not for its brilliance, would seem like egoism. Both are concerned with being unconventional, and with shaking up their respective establishments. Both are passionately fond of the landscapes they grew up in, and delight in using these scenes as a setting for their work. And both are interested, in their own ways, in depictions of the female form; in redefining female beauty, portraying it in terms that are less pristine and therefore less feigned.

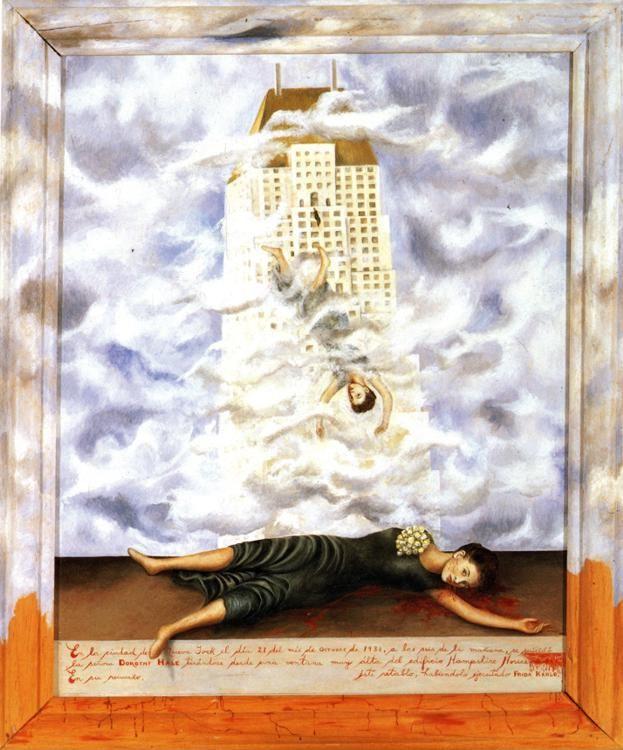

You have only to look at a Kahlo portrait (like the one above) though, to see where the comparison breaks down. For where Courbet's paintings radiate a sort of lazy, unconscious sensuality, his subjects often portrayed asleep or resting, Kahlo's dominant mode is confrontation. In painting after painting, the people in Kahlo's paintings stare back at you with a directness that seems almost a challenge. Kahlo forces us to pay attention to her images by having them pay attention to us - her paintings do not so much invite our gaze as demand it. In the dozen or so self-portraits that are included in the exhibition what you sense is not so much exhibitionism but a kind of generalized narcissism - this is a woman who is in love with the idea of looking directly at the world and having it stare right back [1]. And it's not only in the self-portraits that you feel this - nowhere is this sense of engagement more pronounced than in Kahlo's glorious portrayal of the Suicide of Dorothy Hale (below) in which the still open eyes of the corpse in the foreground glare back at you, their expression trapped somewhere between appeal and accusation, concentrated into an intensity that seems to deny Death itself.

Not that the expressions on her subject's faces is the only thing confrontational about Kahlo. The unflinchingness of her vision informs the content of what she paints: whether it's her

famous depiction of a miscarriage in Henry Ford Hospital - a woman (Kahlo) marooned on a blood soaked bed in the middle of a barren plain, surrounded by a surrealist constellation of images, the ribbons of blood connecting them to her womb turning the whole scene into a grotesque May pole dance - or the almost bathetically macabre A Few Small Nips with its bloodbath spilling onto the frame, Kahlo seems determined to embrace all that is visceral and cathartic in the human experience. What shocks about these paintings is not just the subjects they depict, but the fact that Kahlo is willing to inflict such violence on the female body (and by association, on herself) while continuing to identify with it - her refusal to distance herself from the victim, from the pain. To see the savage dislocation of Kahlo's heart in the Two Fridas, or the ruined spectacle of Kahlo's body in The Broken Column (below) is to witness a kind of divine masochism, a strip-mining of the self in the service of art that is as disturbing as it is courageous. R.S. Thomas speaks of an "impulse to conceal your wounds / from her and from a bold public / given to pry" - Kahlo it seems, has no such impulse, and it is this, coupled with the sureness of her visual instinct, that makes her unforgettable.

famous depiction of a miscarriage in Henry Ford Hospital - a woman (Kahlo) marooned on a blood soaked bed in the middle of a barren plain, surrounded by a surrealist constellation of images, the ribbons of blood connecting them to her womb turning the whole scene into a grotesque May pole dance - or the almost bathetically macabre A Few Small Nips with its bloodbath spilling onto the frame, Kahlo seems determined to embrace all that is visceral and cathartic in the human experience. What shocks about these paintings is not just the subjects they depict, but the fact that Kahlo is willing to inflict such violence on the female body (and by association, on herself) while continuing to identify with it - her refusal to distance herself from the victim, from the pain. To see the savage dislocation of Kahlo's heart in the Two Fridas, or the ruined spectacle of Kahlo's body in The Broken Column (below) is to witness a kind of divine masochism, a strip-mining of the self in the service of art that is as disturbing as it is courageous. R.S. Thomas speaks of an "impulse to conceal your wounds / from her and from a bold public / given to pry" - Kahlo it seems, has no such impulse, and it is this, coupled with the sureness of her visual instinct, that makes her unforgettable.

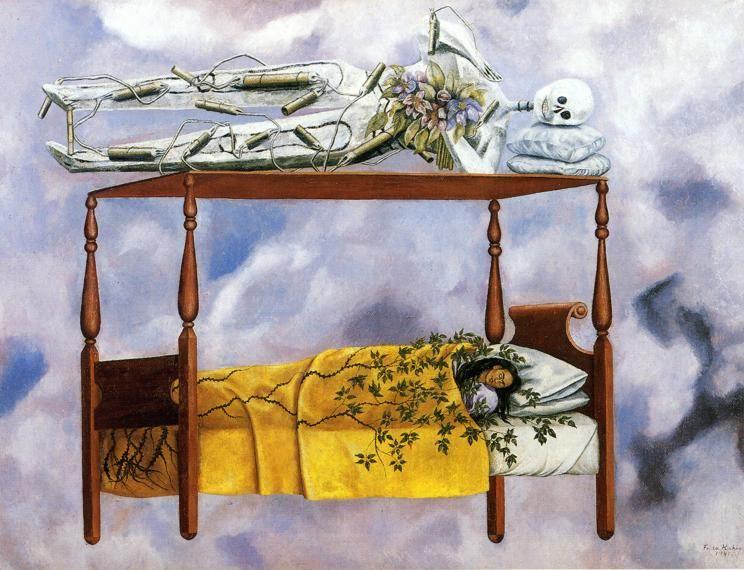

For all the virtues of Kahlo's more passionate work, though, the paintings I prefer are the ones where intensity is balanced with restraint, so that the work, without losing its focus on the themes of death and suffering, depicts these in subtler ways, juxtaposing the stately with the macabre, and producing images that are the more shocking for the contrast. Two Fridas is a good example of this, the figures themselves seem composed, almost preternaturally so, suggesting nothing so much as a traditional portrait of two sisters sitting side by side, so that the effect of the heart torn out from one's chest is amplified. Girl with a Death Mask has a similar effect - the promised innocence of the little girl's figure, daintily clutching a flower in it hand is shockingly belied by the skull of the face. Most shocking of all, though, in its repressed, almost invisible horror, is The Deceased Dimas Rosas Aged Three (below). The image by itself suggests no violence - the central figure seems content and king-like, with its tinsel crown, its scepter like flower, its satisfied, almost complacent expression. It takes a moment for reality to seep in - what you are looking at is not some smug regent but the corpse of a three year old child, complete with poignant little toes pointing into the air and a circle of plucked flowers, the single note of outrage in the whole scene a black and white image of a Christ-like figure tied to a post placed on the pillow by the girl's head.

The Philadelphia Art Museum exhibition is a splendid collection of Kahlo's work, including many of her finest and most famous paintings, covering the full range of her work from the

baroque, intricately programmatic visions of Moses and My Dress Hangs There (right) to her still life of Pitahayas, and showcasing many of Kahlo's abiding themes - the emphasis on linkages and bloodlines (most vividly seen, perhaps, in Family Tree), the repeated motif of exposed roots. Much of what I saw was familiar (though it's always a treat to see paintings like Dream - left - and

baroque, intricately programmatic visions of Moses and My Dress Hangs There (right) to her still life of Pitahayas, and showcasing many of Kahlo's abiding themes - the emphasis on linkages and bloodlines (most vividly seen, perhaps, in Family Tree), the repeated motif of exposed roots. Much of what I saw was familiar (though it's always a treat to see paintings like Dream - left - and  the Love Embrace of the Universe in the original - since reproductions simply don't do them justice), but I also made a number of new discoveries, including the anthropomorphic The Flower of Life (below) and a hauntically delicate portrait of a young girl placed between the sun and the moon (which I can't seem to find online).

the Love Embrace of the Universe in the original - since reproductions simply don't do them justice), but I also made a number of new discoveries, including the anthropomorphic The Flower of Life (below) and a hauntically delicate portrait of a young girl placed between the sun and the moon (which I can't seem to find online). That painting, though painted later, seems like a premonition of what is, perhaps, Kahlo's most indelible self-portrait, and the painting that best sums up her work. In Self-Portrait on the Border between Mexico and the United States (below) Kahlo stands on the margin of two worlds - the land of primal gods and ruined dreams and the land of modernism with its robot-like pipe figures, its electrical vegetation and concrete towers. Placed between these two landscapes, Kahlo herself seems an enigmatic and contradictory figure, the pink ruffled dress and elbow length gloves at odds with the revolutionary air of the casually held cigarette and the Mexican flag - as though she had been dragged away from a party to face, coolly, a firing squad. Seen three quarters of a century after it was painted it is the portrait of an iconoclast, a female colossus, who stands on the border not between Mexico and the United States but between the past and the future, myth and reality. And it is emblematic of everything Kahlo has come to mean, that her expression as she stands there is one of fierce certainty, eyebrows arched, mouth set in hard, proud line, lucid eyes staring right back at you.

That painting, though painted later, seems like a premonition of what is, perhaps, Kahlo's most indelible self-portrait, and the painting that best sums up her work. In Self-Portrait on the Border between Mexico and the United States (below) Kahlo stands on the margin of two worlds - the land of primal gods and ruined dreams and the land of modernism with its robot-like pipe figures, its electrical vegetation and concrete towers. Placed between these two landscapes, Kahlo herself seems an enigmatic and contradictory figure, the pink ruffled dress and elbow length gloves at odds with the revolutionary air of the casually held cigarette and the Mexican flag - as though she had been dragged away from a party to face, coolly, a firing squad. Seen three quarters of a century after it was painted it is the portrait of an iconoclast, a female colossus, who stands on the border not between Mexico and the United States but between the past and the future, myth and reality. And it is emblematic of everything Kahlo has come to mean, that her expression as she stands there is one of fierce certainty, eyebrows arched, mouth set in hard, proud line, lucid eyes staring right back at you.

[1] I am reminded of a line from Berryman - "He stared at ruin. Ruin stared straight back."

Wednesday, May 07, 2008

Wright Off

While I've largely stopped paying attention to the farce that the contest for the Democratic nomination has turned into, I can't help commenting on the Rev. Wright controversy and Obama's response to it.

The general consensus, at least among Obama's critics, seems to be that in finally coming out and explicitly condemning Rev. Wright for his ridiculous remarks Obama is going against his natural inclination in deference to public opinion polls. He is, in other words, playing politics - choosing to distance himself from a figure who has clearly become a political liability - and that his 'real' feelings were those expressed in his earlier response to the Wright controversy, when he distanced himself from some of Rev. Wright's more extreme ideas, but refused to condemn the man himself.

It seems to me equally plausible, however, that the opposite is true. In particular, it seems to me that the truth about Obama may be both better and (politically speaking) worse than the conventional interpretation would suggest. This is pure speculation, obviously, but my suspicion is that Obama is precisely the kind of person who's intelligent enough to be able to separate the content of religion from the power associated with it, and use the latter while ignoring the former. In other words, Obama may not have paid attention to / been outraged by Rev. Wright's ideas not because he agreed with them, but because he (Obama) is not the kind of person who takes anything a preacher says seriously. I mean, it's all nonsense, isn't it? How is believing that AIDS is part of a conspiracy against black people any sillier than believing in, say, immaculate conception? Obama wasn't sitting in that church because he wanted to get spiritual or moral guidance or anything like that, he was sitting in that church because being seen as part of that community would get him votes.

The trouble, of course, is that there's no way Obama could ever admit this, even if it were true. No matter how many votes he may lose by being associated with Rev. Wright, he'd lose a great deal more if he were to declare, for instance, that he isn't a religious person, that he sat in church because it was part of engaging with a community and he didn't give a toss what some silly preacher was saying. I personally find the idea of a US President who has no religious faith whatsoever extremely appealing, but I suspect that any candidate who openly admitted this would be dead in the water. So the myth of spiritual guidance and close ties to the faith must be maintained, even at the cost of associating with Rev. Wright.

Seen in this (entirely hypothetical) light, it's Obama's earlier response to the Wright controversy, however skilfully delivered, that is, in fact, the more 'political', which is to say the less sincere. What Obama was trying to do, under the guise of taking a balanced, measured perspective, was to play both sides - appease voters appalled by the specter of Rev. Wright without alienating those who might see a strong repudiation of Rev. Wright as an ungrateful betrayal, an attempt on Obama's part to divorce himself from the very roots that are the source of their support for him.

The irony here is that Obama may be the victim of his own eloquence: because his initial response to the Wright controversy - which may have been just a wishy-washy attempt to pander to multiple constituencies at the same time - came across as so genuine, his more recent stand on the issue (if one may call it that) has come to be perceived as weak and reluctant, a compromise driven by calculative necessity, rather than what it may really be - an expression of the man's true feelings, relieved of the need to try and soft-pedal the issue by either the realization that the more 'political' strategy was untenable, or a sense that the Rev. had made himself enough of a pariah so that he could be repudiated without causing much damage.

Again, I emphasize that this is all speculation - I'm not saying (because I obviously can't prove) that any of this is true, just that it provides a counterpoint to the usual interpretation of Obama's actions and an alternative storyline that fits all the facts but gives us a completely different picture of the man himself than the one the media has been giving us.

The general consensus, at least among Obama's critics, seems to be that in finally coming out and explicitly condemning Rev. Wright for his ridiculous remarks Obama is going against his natural inclination in deference to public opinion polls. He is, in other words, playing politics - choosing to distance himself from a figure who has clearly become a political liability - and that his 'real' feelings were those expressed in his earlier response to the Wright controversy, when he distanced himself from some of Rev. Wright's more extreme ideas, but refused to condemn the man himself.

It seems to me equally plausible, however, that the opposite is true. In particular, it seems to me that the truth about Obama may be both better and (politically speaking) worse than the conventional interpretation would suggest. This is pure speculation, obviously, but my suspicion is that Obama is precisely the kind of person who's intelligent enough to be able to separate the content of religion from the power associated with it, and use the latter while ignoring the former. In other words, Obama may not have paid attention to / been outraged by Rev. Wright's ideas not because he agreed with them, but because he (Obama) is not the kind of person who takes anything a preacher says seriously. I mean, it's all nonsense, isn't it? How is believing that AIDS is part of a conspiracy against black people any sillier than believing in, say, immaculate conception? Obama wasn't sitting in that church because he wanted to get spiritual or moral guidance or anything like that, he was sitting in that church because being seen as part of that community would get him votes.

The trouble, of course, is that there's no way Obama could ever admit this, even if it were true. No matter how many votes he may lose by being associated with Rev. Wright, he'd lose a great deal more if he were to declare, for instance, that he isn't a religious person, that he sat in church because it was part of engaging with a community and he didn't give a toss what some silly preacher was saying. I personally find the idea of a US President who has no religious faith whatsoever extremely appealing, but I suspect that any candidate who openly admitted this would be dead in the water. So the myth of spiritual guidance and close ties to the faith must be maintained, even at the cost of associating with Rev. Wright.

Seen in this (entirely hypothetical) light, it's Obama's earlier response to the Wright controversy, however skilfully delivered, that is, in fact, the more 'political', which is to say the less sincere. What Obama was trying to do, under the guise of taking a balanced, measured perspective, was to play both sides - appease voters appalled by the specter of Rev. Wright without alienating those who might see a strong repudiation of Rev. Wright as an ungrateful betrayal, an attempt on Obama's part to divorce himself from the very roots that are the source of their support for him.

The irony here is that Obama may be the victim of his own eloquence: because his initial response to the Wright controversy - which may have been just a wishy-washy attempt to pander to multiple constituencies at the same time - came across as so genuine, his more recent stand on the issue (if one may call it that) has come to be perceived as weak and reluctant, a compromise driven by calculative necessity, rather than what it may really be - an expression of the man's true feelings, relieved of the need to try and soft-pedal the issue by either the realization that the more 'political' strategy was untenable, or a sense that the Rev. had made himself enough of a pariah so that he could be repudiated without causing much damage.

Again, I emphasize that this is all speculation - I'm not saying (because I obviously can't prove) that any of this is true, just that it provides a counterpoint to the usual interpretation of Obama's actions and an alternative storyline that fits all the facts but gives us a completely different picture of the man himself than the one the media has been giving us.

Monday, May 05, 2008

Courbet at the Met

Was in NYC over the weekend, checking out (among other things) the Courbet exhibit at the Met, and was amused to find this painting tucked coyly away in a dimly lit gallery with a sign outside it warning visitors that the section contained explicit sexual images.

I suppose the Met has all sorts of legal issues it needs to be concerned about, but I can't help wondering how Courbet would have felt about such prudishness. I mean, it kind of destroys the point, doesn't it?

To begin with, the exhibition seemed a little underwhelming. Courbet's portraits - which make up the first few galleries - are excellent, of course, but coming so soon after the Met's exhibition of the Dutch masters it was hard not to see the influence of Rembrandt and Hals in Courbet's work, and they suffered by comparison. The ones I liked best (other than the familiar Desperate Man) was the Man Made Mad by Fear, with its Dali like depiction of a human figure poised on the edge of the abyss and Courbet's charming portrait of Proudhon, where a startlingly modern-looking figure of the painter is set against a backdrop that seems quaint and artificial, the blandness of the surroundings (those ubiquitous children) emphasizing, for me, the impression of Proudhon's living presence.

it was hard not to see the influence of Rembrandt and Hals in Courbet's work, and they suffered by comparison. The ones I liked best (other than the familiar Desperate Man) was the Man Made Mad by Fear, with its Dali like depiction of a human figure poised on the edge of the abyss and Courbet's charming portrait of Proudhon, where a startlingly modern-looking figure of the painter is set against a backdrop that seems quaint and artificial, the blandness of the surroundings (those ubiquitous children) emphasizing, for me, the impression of Proudhon's living presence.

The other fascinating thing about Courbet is the subtle and not to subtle way in which he emphasizes the scale of his female figures, making them seem larger than life. In paintings like Young Ladies of the Village, The Source and The Woman in the Waves (below) Courbet sets the female form in settings that are at once realistic and diminished, using perspective to achieve an effect that is at once mythic and breathtakingly real.

The most impressive part of the exhibition for me, though, were the final galleries, that contained both Courbet's landscapes (including a set of immediate and powerful depictions of waves as well as the glorious harmony of brown and orange that is his Source of the Loue below) as well as his 'nature' paintings (including Fox in the Snow and Trout).

What stood out for me, going over the exhibition in my head afterwards, was the incredible range that Courbet's work encompasses, ranging all the way from the great Dutch and Flemish masters through the Impressionists and on to the first intimations of Surrealism. For an exhibition by a single painter to make one think of Rembrandt, Reubens, Renoir, Cezanne and Dali is a considerable achievement.

Note: Coming up (eventually) - posts on Poussin, Jasper Johns, the Tribeca Film Festival and Wajda's glorious Katyn. I love New York.

I suppose the Met has all sorts of legal issues it needs to be concerned about, but I can't help wondering how Courbet would have felt about such prudishness. I mean, it kind of destroys the point, doesn't it?

To begin with, the exhibition seemed a little underwhelming. Courbet's portraits - which make up the first few galleries - are excellent, of course, but coming so soon after the Met's exhibition of the Dutch masters

it was hard not to see the influence of Rembrandt and Hals in Courbet's work, and they suffered by comparison. The ones I liked best (other than the familiar Desperate Man) was the Man Made Mad by Fear, with its Dali like depiction of a human figure poised on the edge of the abyss and Courbet's charming portrait of Proudhon, where a startlingly modern-looking figure of the painter is set against a backdrop that seems quaint and artificial, the blandness of the surroundings (those ubiquitous children) emphasizing, for me, the impression of Proudhon's living presence.

it was hard not to see the influence of Rembrandt and Hals in Courbet's work, and they suffered by comparison. The ones I liked best (other than the familiar Desperate Man) was the Man Made Mad by Fear, with its Dali like depiction of a human figure poised on the edge of the abyss and Courbet's charming portrait of Proudhon, where a startlingly modern-looking figure of the painter is set against a backdrop that seems quaint and artificial, the blandness of the surroundings (those ubiquitous children) emphasizing, for me, the impression of Proudhon's living presence.

The other fascinating thing about Courbet is the subtle and not to subtle way in which he emphasizes the scale of his female figures, making them seem larger than life. In paintings like Young Ladies of the Village, The Source and The Woman in the Waves (below) Courbet sets the female form in settings that are at once realistic and diminished, using perspective to achieve an effect that is at once mythic and breathtakingly real.

The most impressive part of the exhibition for me, though, were the final galleries, that contained both Courbet's landscapes (including a set of immediate and powerful depictions of waves as well as the glorious harmony of brown and orange that is his Source of the Loue below) as well as his 'nature' paintings (including Fox in the Snow and Trout).

What stood out for me, going over the exhibition in my head afterwards, was the incredible range that Courbet's work encompasses, ranging all the way from the great Dutch and Flemish masters through the Impressionists and on to the first intimations of Surrealism. For an exhibition by a single painter to make one think of Rembrandt, Reubens, Renoir, Cezanne and Dali is a considerable achievement.

Note: Coming up (eventually) - posts on Poussin, Jasper Johns, the Tribeca Film Festival and Wajda's glorious Katyn. I love New York.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)