Sunday, June 27, 2010

Rio

To enter Rio is to enter Byzantium. The young in one another's arms, the dolphin-torn sea. Just walking the streets here I feel ragged, stick-like, which is to say I am conscious the city is more attitude than place, is the catalyst for an emotional reaction to which leaves me inert. Everywhere I look people are living out their test-tube vacations, bubbles of laughter fizzing from their eyes.

Friday, June 18, 2010

Thursday, June 17, 2010

Attribution Error in the Blogosphere

To credit all positive comments to your own perspicacity and talent, and blame all negative comments on the stupidity and prejudice of your commenters.

Well said

"For many centuries in the Western tradition, how well you expressed a position corresponded closely to the credibility of your argument. Rhetorical styles might vary from the spartan to the baroque, but style itself was never a matter of indifference. And “style” was not just a well-turned sentence: poor expression belied poor thought. Confused words suggested confused ideas at best, dissimulation at worst."

That's Tony Judt over at the NYRB blog. It's a point of view I happen to wholeheartedly agree with, if only because empirical observation proves it to be true. People who write badly think badly. Every now and then I'll grit my teeth and try to read something that's ungrammatical and badly structured because what it says might be 'important' (for a particularly egregious recent example, see here), and almost without exception the piece in question will turn out to be illogical, incoherent or just plain silly.

(This doesn't work in reverse, of course. The most exquisite prose may make no sense whatsoever).

I think the point is that lucid writing is a byproduct of a process of careful thought. The more deeply you think about an issue, the more word choices start to matter, the clearer the purpose of each phrase and each sentence becomes, and the more the sentences themselves fall into a natural order. Clarity of thought produces clarity of writing.

It's a standard too few people seem to care about.

Spending Time

If it were possible to spend what one does not own, I would trade the restlessness of the ocean for this moment of silence, you and I alone on the balcony, high above the traffic, afraid to look down. You say you are afraid of falling. I say I am afraid of heights. What we have in common is that we understand these two fears are not the same. The balcony is a cage of glass and air. We both wish we didn't have to fly.

Tuesday, June 01, 2010

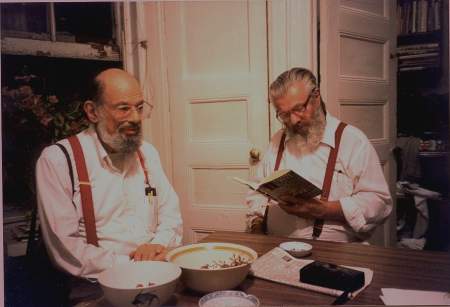

Peter Orlovsky 1933 - 2010

No, the madness didn't destroy him. He outlived them all: Cassady, Kerouac, Allen himself. Survived the drugs and the alcohol, the sex and the protests, to die unoutrageously of lung cancer at the age of 76.

No, he was not his animal. In the poems he is an altogether quieter, more domestic presence, a shadow you barely see. And yet he is there on the front page of Kaddish, an angel of grief, and there again twenty years later, lending his back and strong shoulders to Ginsberg Sr., being told not to grow old, and (as we now know) ignoring the advice. He is there in the elegies to O'Hara and Cassady, lending his sympathetic ear and voice to the general sorrow. Again and again, when death intercedes, he is there to comfort, console.

When they first met, half a century ago, Allen wrote:

and here they are, 40 years later, two old men sitting in companionable silence around a dining table; two bowls, chipped and almost empty, laid side by side.

No, he wasn't the best mind of his generation. But what he was, and what he had, is hard not to envy. And if even some of the power of those poems draws strength from his presence, that is more than most of us can hope to contribute.

Notes:

Ginsberg quote taken from 'Malest Cornifici Tuo Catullo' . Ginsberg and Orlovsky image taken from this piece by Gordon Ball in Jacket, July 2007.

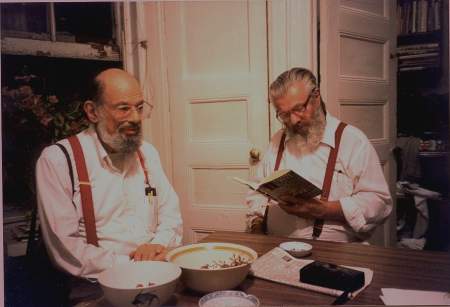

No, he was not his animal. In the poems he is an altogether quieter, more domestic presence, a shadow you barely see. And yet he is there on the front page of Kaddish, an angel of grief, and there again twenty years later, lending his back and strong shoulders to Ginsberg Sr., being told not to grow old, and (as we now know) ignoring the advice. He is there in the elegies to O'Hara and Cassady, lending his sympathetic ear and voice to the general sorrow. Again and again, when death intercedes, he is there to comfort, console.

When they first met, half a century ago, Allen wrote:

"discovered a new young cat,

and my imagination of an eternal boy

walks on the streets of San Francisco,

handsome, and meets me in cafetarias

and loves me."

and here they are, 40 years later, two old men sitting in companionable silence around a dining table; two bowls, chipped and almost empty, laid side by side.

No, he wasn't the best mind of his generation. But what he was, and what he had, is hard not to envy. And if even some of the power of those poems draws strength from his presence, that is more than most of us can hope to contribute.

Notes:

Ginsberg quote taken from 'Malest Cornifici Tuo Catullo' . Ginsberg and Orlovsky image taken from this piece by Gordon Ball in Jacket, July 2007.

Sunday, May 30, 2010

That poetry makes nothing happen

may be one of its chief delights.

To create something that has immediate and practical application is to be a cog in the utilitarian machine. But to make something that has neither definable quality nor discernible purpose is to experience first hand the joy of original creation.

Adam gave names to all the animals. We give the animal back to the names.

***

As you may have already figured out, it's been a particularly rewarding weekend, poetry reading wise - D.A. Powell's Cocktails, Rachel Zucker's Bad Wife Handbook and Armantrout's Up to Speed, with Geoffrey Hill's Selected Poems to follow. Happiness.

To create something that has immediate and practical application is to be a cog in the utilitarian machine. But to make something that has neither definable quality nor discernible purpose is to experience first hand the joy of original creation.

Adam gave names to all the animals. We give the animal back to the names.

***

As you may have already figured out, it's been a particularly rewarding weekend, poetry reading wise - D.A. Powell's Cocktails, Rachel Zucker's Bad Wife Handbook and Armantrout's Up to Speed, with Geoffrey Hill's Selected Poems to follow. Happiness.

E-2 Brutus

Yet more evidence of the NY Times inability to do math / willingness to turn almost anything into a puff piece:

This from a piece that talks about "the forgotten story of immigration" and the trend towards more E-2 application rejections.

Never mind the deduction of a 'trend' from three data points. Never mind that without more information it's impossible to tell whether an 8 percentage point drop in approvals is significant and / or whether 91 percent in 2008 was average or high. Never mind that it seems fairly reasonable, given what the economy has been like the last few years, to suppose that an additional 10% or so of people may have seen a drop in their income which would put them in a marginal income category.

Even if you buy these numbers completely, we're still talking about 8, 468 requests in 2.5 years = 1,700 requests in the last six months, 8% of which is 136. That's all of 136 additional people who've been denied visas this year as a result of this frightening new trend. Maybe there's a reason it's a forgotten story.

Over the last two and a half years, 8,468 requests for E-2 extensions have been filed, and their approval rate does appear to have dropped, according to figures provided by William G. Wright, a spokesman for the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. So far in the 2010 fiscal year, he said, 82 percent of the applications have been approved. In 2009, 84 percent were approved, and in 2008, 91 percent.

This from a piece that talks about "the forgotten story of immigration" and the trend towards more E-2 application rejections.

Never mind the deduction of a 'trend' from three data points. Never mind that without more information it's impossible to tell whether an 8 percentage point drop in approvals is significant and / or whether 91 percent in 2008 was average or high. Never mind that it seems fairly reasonable, given what the economy has been like the last few years, to suppose that an additional 10% or so of people may have seen a drop in their income which would put them in a marginal income category.

Even if you buy these numbers completely, we're still talking about 8, 468 requests in 2.5 years = 1,700 requests in the last six months, 8% of which is 136. That's all of 136 additional people who've been denied visas this year as a result of this frightening new trend. Maybe there's a reason it's a forgotten story.

Saturday, May 29, 2010

They learn in suffering what they teach in song

"Here's the thing. I am basically willing to do anything. I'm basically willing to do anything to come up with a really good poem. I want to do that. That's may goal in life. And it hasn't happened. I've waited patiently. Sometimes I've waited impatiently. Sometimes I've 'striven'. I've made some acceptable poems - poems that have been accepted in a literal sense. But not one single really good poem.

When I look at the lives of the poets, I understand what's wrong with me. They were willing to make sacrifices that I'm not willing to make. They were so tortured, so messed up.

I'm only a little messed up. I'm tortured to the point where I don't sleep very well sometimes, and I don't answer mail as I should. Sometimes I feel a languor of spirit when I get an email asking me to do something. Also, I've run up a significant credit-card debt. But that's not real self-torture. I mean, if you stand back from my life just a little - maybe thirty-five yards - I am a completely conventional person. I drive mostly within the fog lines. My life is seldom in crisis...I'm in considerable pain but this little crisis of mine does not resemble the crises that Ted Roethke or Louise Bogan went through, or James Wright, or Tennyson, or Elizabeth Barrett Browning, with her laudanum. Or Poe."

- Nicholson Baker, The Anthologist

One of the chief delights of The Anthologist (and it's a book chock full of little delights - not a particularly good novel as a whole, but brimming with nice little touches - how can you not be charmed by a book that contains the sentence "Swinburne was like the application of too much fertilizer to a very green lawn"?) is its marvelous portrayal of the inherently quixotic nature of the poetic enterprise. The way the decision to write poetry is both ridiculous and heroic, with the former being the cause of the latter. We believe our poems are not good enough, can never be good enough, but we go on writing them anyway, and insist on comparing ourselves to precisely those we can never equal. Self-doubt and self-importance being the lift and drag that hold the viewless wings of poesy in balance.

Suffering does not make for great poetry. If it did, Gitmo would have the world's finest MFA program, the asylums would overflow with the murmur of lyric stanzas, and great bards would run riot through the streets of Haiti. If anything suffering, real suffering, makes poetry both impossible and irrelevant.

Where does that leave our familiar specter, the tortured poet? It is not suffering that makes poets great, but great poets who make suffering real. Make it convincing. Even to themselves.

P.S. Post title taken from Shelley.

Dryden's Tea Party

Reading Dryden this weekend, I am struck by how eerily contemporary the politics in his poems seems: the uneasy alliance between anti-government paranoia, corporate interest, religious fundamentalism and xenophobic bigotry that comprises what we now call the hard Right.- John Dryden, from Absalom and Achitophel

- Whose differing Parties he could wisely Joyn,

- For several Ends, to serve the same Design.

- The Best, and of the Princes some were such,

- Who thought the power of Monarchy too much:

- Mistaken Men, and Patriots in their Hearts;

- Not Wicked, but Seduc'd by Impious Arts.

- By these the Springs of Property were bent,

- And wound so high, they Crack'd the Government.

- The next for Interest sought t'embroil the State,

- TO sell their Duty at a dearer rate;

- And make their Jewish Markets of the Throne,

- Pretending puclick Good, to serve their own.

- Others thought Kings an useless heavy Load,

- Who Cost too much, and did too little Good.

- These were for laying Honest David by,

- On Principles of pure good Husbandry.

- With them Joyn'd all th' Haranguers of the Throng,

- That thought to get Preferment by the Tongue.

- Who follows next, a double Danger bring,

- Not only hating David, but the King,

- The Solymæan Rout; well Verst of old,

- In Godly Faction, and in Treason bold;

- Cowring and Quaking at a Conqueror's Sword,

- But Lofty to a Lawfull Prince Restor'd;

- Saw with Disdain an Ethnick Plot begun,

- And Scorn'd by Jebusites to be Out-done.

- Hot Levites Headed these; who pul'd before

- From the Ark, which in the Judges days they bore,

- Resum'd their Cant, and with a Zealous Cry,

- Pursu'd their old belov'd Theocracy.

- Where Sanhedrin and Priest inslav'd the Nation,

- And justifi'd their Spoils by Inspiration;

- For who so fit for Reign as Aarons's race,

- If once Dominion they could found in Grace?

- These led the Pack; tho not of surest scent,

- Yet deepest mouth'd against the Government.

- A numerous Host of dreaming Saints succeed;

- Of the true old Enthusiastick breed;

- 'Gainst Form and Order they their Power employ;

- Nothing to Build and all things to Destroy.

- But far more numerous was the herd of such,

- Who think too little, and who talk too much.

- These, out of meer instinct, they knew not why,

- Ador'd their fathers God, and Property:

- And, by the same blind benefit of Fate,

- The Devil and the Jebusite did hate:

- Born to be sav'd, even in their own despight;

- Because they could not help believing right.

- Such were the tools; but a whole Hydra more

- Remains, of sprouting heads too long, to score.

Does the perspicacity of the old masters come from a unique insight into the human condition, or is it just that history is so inherently repetitive that a moderately competent description of one age echoes familiarly in another? Either thought is depressing, though the former suggests a personal failure, and the latter a more general one.

These poems also render a much finer sense of the political in poetry, reminding us that the political poem can be more than an act of witness or protest, more than an impassioned outcry against perceived wrong. In the hands of Dryden, or Marvell, or (for that matter) Lucan, it can be a thoughtful argument for a point of view, laying out intelligently and forcefully the causes and consequences of the big picture.

Sunday, May 23, 2010

Isle of the Dead

No, the dead are not an island. They are the sea restless, encircling. The sound of shells held to our ears.

It is we who are marooned. We go about our everyday business and barely notice their presence surrounding us. Only now and then, when we feel the tug of the tide calling us, do we go down to the water, stare out across the impossible distance, and wonder: "Is there life beyond?"

It is we who are marooned. We go about our everyday business and barely notice their presence surrounding us. Only now and then, when we feel the tug of the tide calling us, do we go down to the water, stare out across the impossible distance, and wonder: "Is there life beyond?"

Saturday, May 22, 2010

Jesus vs. Christ

The essence of faith is negative choice.

To accept one's fate implies more than resignation, it implies a recognition of one's capability for change and the decision not to use that capability. A man who lives in poverty because he has to is a beggar, a man who chooses poverty is a saint.

***

Adam Gopnik, in this week's New Yorker, argues that the double helix of the tolerant and humble Jesus and the miracle-working, apocalypse-preaching Christ is fundamental to the DNA of Christianity [1]. As he puts it:

To accept one's fate implies more than resignation, it implies a recognition of one's capability for change and the decision not to use that capability. A man who lives in poverty because he has to is a beggar, a man who chooses poverty is a saint.

***

Adam Gopnik, in this week's New Yorker, argues that the double helix of the tolerant and humble Jesus and the miracle-working, apocalypse-preaching Christ is fundamental to the DNA of Christianity [1]. As he puts it:

This fixed, steady twoness at the heart of the Christian story can’t be wished away by liberal hope any more than it could be resolved by theological hair-splitting. Its intractability is part of the intoxication of belief. It can be amputated, mystically married, revealed as a fraud, or worshipped as the greatest of mysteries. The two go on, and their twoness is what distinguishes the faith and gives it its discursive dynamism

It seems to me that there is a good reason for this [2], which is simply that for the suffering of Jesus to be meaningful, he must possess the powers of Christ, and choose not to use them. Tolerance requires authority, self-sacrifice requires the ability to escape.

Notes

[1] The whole thing being basically a good cop / bad cop act, which would make the Gospels the earliest buddy movies.

[2] Aside from the obvious dramatic interest that the tension creates, making the figure of Christ more enigmatic and therefore more engaging. Not to mention flexible.

Notes

[1] The whole thing being basically a good cop / bad cop act, which would make the Gospels the earliest buddy movies.

[2] Aside from the obvious dramatic interest that the tension creates, making the figure of Christ more enigmatic and therefore more engaging. Not to mention flexible.

Friday, May 21, 2010

The sound of one hand...

...playing the piano. Ravel's glorious Piano Concerto for Left Hand (here performed by Richter) which I heard played this evening in a superb performance by Marc-Andre Hamelin and the Minnesota Orchestra.

Other highlights of the evening included Strauss' Don Juan (which puts a whole new spin on horniness!) and a passionate rendition of Ravel's brilliantly subversive La Valse under the baton of Gilbert Varga, bubbles of disquiet under the swirling surface of the music.

Thursday, May 20, 2010

Lies

What if every truth was a lie we couldn't see through? And every lie we saw through a truth in disguise?

What if the purity of heaven meant an eternity of not touching, an infinity of white.

No protest but silence. No context but the light. Books filled with pages too wise for words.

What if the purity of heaven meant an eternity of not touching, an infinity of white.

No protest but silence. No context but the light. Books filled with pages too wise for words.

Monday, May 17, 2010

Marsyas born again

si come quando Marsia traesti

de la vagina de le membra sue

- Dante, Paradiso I.20-21

Life as gestation. The soul ripped bloody and crying from the flesh.

Hard to imagine Apollo as a midwife. Hard to believe in the waiting room's holy trinity. The father, the son, the holy smoke.

What is hell but the desire to return to the body, its warm and secret cave?

Sunday, May 16, 2010

La gopi e mobile

Listening to La Traviata right after reading Denise Levertov's translations of songs in praise of Krishna, it occurs to me that this whole Radha-Krishna thing would make such a brilliant opera. I mean, Radha is the quintessential Puccini heroine (whiny, self-sacrificing, terrible taste in men) and Krishna bears a strong family resemblance to the Duke in Rigoletto. Just add the baritone voices of Balaram and Kans, throw in a lot of flute solos and some liberal use of cowbells, and before you can say Figaro three times very fast you've got a melodrama that is guaranteed to have them in tears by Act III.

Plus, can you imagine the faces of the Shiv Sena goons when they discover their beloved god looking something like this.

Plus, can you imagine the faces of the Shiv Sena goons when they discover their beloved god looking something like this.

Shelf Life

"My books, a bizarre accumulation of the learning and knowledge of all eras: history, travel, religions, cabala, astrology....There is enough here to drive a wise man mad; we shall see whether there is also enough to make a madman wise."

- Gerard de Nerval, Aurelia (translated by Kendall Lappin)

- Gerard de Nerval, Aurelia (translated by Kendall Lappin)

Deflection

Heaven in a wild flower

Don't go wandering in the park; there's a garden deep inside you.

Sit at the petaled heart of the lotus; you can see the infinite.

- Kabir (translation mine)

The more I think about it, the more it seems to me that Kabir and Blake would have got along like a heaven on fire.

Note: The Kabir in the original:

Baagon na jaa re na jaa, teri kaaya mein gulzaar

Sahas-kanval par baith ke tu dekhe roop apaar.

Saturday, May 15, 2010

Manguel on Reading

Just finished reading Alberto Manguel's A Reader on Reading, which turns out to be both a fascinating and dissatisfying read.

In many ways, Manguel is the epitome of the intelligent reader: his knowledge of books is extensive, his tastes broad, if not quite eclectic, his engagement profound, his appreciation heartfelt. He's the kind of reader who makes writing seem worthwhile.

Which is why it's disappointing that A Reader on Reading is not a more compelling book. Oh, it's interesting enough: the individual essays are cogently argued and exquisitely written, combining personal anecdotes [1] with insightful commentary. But underlying these essays is a larger argument, a defense (in the traditional sense) of reading, which runs something like this:

Reading - by which Manguel means serious reading, the kind that challenges the reader - matters because it is critical to human development. Critical, thoughtful reading expands our imagination, deepens our sympathy, and enhances our ability to think clearly and analytically; abilities that are essential to the flowering of the self, and, by extension, to the creation and preservation of a just and equitable social order. If all moral failure is first a failure of the imagination, then reading is the essential antidote; the elixir by which we may be transformed into better citizens and better human beings.

For this elixir to take effect, however, two things are required. First, the art of reading must be kept alive. We need readers who understand that reading is no casual undertaking, but a talent that must be honed through rigorous application and experience; readers who understand that great books are often slow and difficult, that it is this that makes them rewarding; readers who are willing to make the effort that reading requires. Second, we need writing that justifies such effort. Not the easy pap of advertising and journalism and mass-produced pulp fiction, all carefully designed to appeal to its audience tastes and confirm them in their prejudices, but books that challenge and frustrate their readers, taking them out of their comfort zones and allowing them to discover the new and unexpected [2].

It's not that I disagree with Manguel's perspective. On the contrary, I'm largely supportive of what he's saying, even if I find some of his opinions a tad reactionary. My problem with this argument is that it strikes me as being too sterile, too somber, too self-important. As Eliot would have it: "Are we then so serious?". Saying that reading matters because it helps us grow as human beings is like saying sex matters because it enables us to reproduce. What's missing from the argument is the profound joy of the act itself, its abiding and overwhelming wonder. As every book-lover knows, to read a great book is to experience an emotional, intellectual and aesthetic transcendence, to be taken out of yourself and then returned to a world that seems both more nuanced and more vivid. The fact that reading has a redeeming social purpose is just gravy, if it served no such purpose it would still be worth championing, if only for the thrill it affords. Because that kind of intensity may be the most the human animal is capable of or can aspire to, and for the great mass of people to be deprived of its magical power is a shame indeed. Beauty needs no justification; it is, and always will be, its own reward.

One could argue that making pleasure the basis of literature's claims plays straight into the hands of the hacks who judge the quality of their books by their popularity. After all, if the purpose of reading is to deliver pleasure, then surely bestsellers are the ones who serve this purpose best. What this ignores, of course, is the quality of the experience. It is important not to confuse entertainment with joy. There may be people for whom reading Dan Brown or Chetan Bhagat is a revelatory and transformative experience, who step away from these authors with their minds alight and their senses on fire. Good for them. But for most people, I suspect, reading these authors is no less or more enjoyable than watching a sitcom on TV or gossiping with their colleagues over lunch. And the point is that reading is capable of delivering so much more. If you've never finished a book and come away with the sense (however fleeting) that the world is different, then you've never truly read a book. And believe me, you're missing out.

In any case, pragmatic considerations are hardly the strong suit of A Reader on Reading. If you're going to try and convert people who don't read seriously or see reading as trivial, writing a book that celebrates Dante, Homer, Borges and Cervantes is hardly the right way to go about it. Nor is extolling the civic importance of reading, which only serves to convert what is a privilege into a duty, what is an indulgence into a chore. I consider myself quite seriously committed to reading, but by the end of Manguel's umpteenth sermon about why reading matters even I was starting to chafe at the bit. There is much to delight in in Manguel's book, but it is a book meant for preaching to the choir, a set of essays by a quintessential book lover that only other book lovers will truly appreciate. Which is why it's frustrating that Manguel, who is clearly passionate about books himself (the man finds solace in a hospital bed re-reading Don Quixote!), confines himself to these dry abstractions in defense of reading, never explicitly acknowledging its more visceral delights.

Notes

[1] The man spent his early years hanging out with Borges! Color me bright green with envy.

[2] Manguel doesn't explicitly spell this out, of course, it's my reading of what he's saying, though I think it's a fairly accurate one. In any case, as Manguel himself would argue, a book is what the reader interprets it to be.

In many ways, Manguel is the epitome of the intelligent reader: his knowledge of books is extensive, his tastes broad, if not quite eclectic, his engagement profound, his appreciation heartfelt. He's the kind of reader who makes writing seem worthwhile.

Which is why it's disappointing that A Reader on Reading is not a more compelling book. Oh, it's interesting enough: the individual essays are cogently argued and exquisitely written, combining personal anecdotes [1] with insightful commentary. But underlying these essays is a larger argument, a defense (in the traditional sense) of reading, which runs something like this:

Reading - by which Manguel means serious reading, the kind that challenges the reader - matters because it is critical to human development. Critical, thoughtful reading expands our imagination, deepens our sympathy, and enhances our ability to think clearly and analytically; abilities that are essential to the flowering of the self, and, by extension, to the creation and preservation of a just and equitable social order. If all moral failure is first a failure of the imagination, then reading is the essential antidote; the elixir by which we may be transformed into better citizens and better human beings.

For this elixir to take effect, however, two things are required. First, the art of reading must be kept alive. We need readers who understand that reading is no casual undertaking, but a talent that must be honed through rigorous application and experience; readers who understand that great books are often slow and difficult, that it is this that makes them rewarding; readers who are willing to make the effort that reading requires. Second, we need writing that justifies such effort. Not the easy pap of advertising and journalism and mass-produced pulp fiction, all carefully designed to appeal to its audience tastes and confirm them in their prejudices, but books that challenge and frustrate their readers, taking them out of their comfort zones and allowing them to discover the new and unexpected [2].

It's not that I disagree with Manguel's perspective. On the contrary, I'm largely supportive of what he's saying, even if I find some of his opinions a tad reactionary. My problem with this argument is that it strikes me as being too sterile, too somber, too self-important. As Eliot would have it: "Are we then so serious?". Saying that reading matters because it helps us grow as human beings is like saying sex matters because it enables us to reproduce. What's missing from the argument is the profound joy of the act itself, its abiding and overwhelming wonder. As every book-lover knows, to read a great book is to experience an emotional, intellectual and aesthetic transcendence, to be taken out of yourself and then returned to a world that seems both more nuanced and more vivid. The fact that reading has a redeeming social purpose is just gravy, if it served no such purpose it would still be worth championing, if only for the thrill it affords. Because that kind of intensity may be the most the human animal is capable of or can aspire to, and for the great mass of people to be deprived of its magical power is a shame indeed. Beauty needs no justification; it is, and always will be, its own reward.

One could argue that making pleasure the basis of literature's claims plays straight into the hands of the hacks who judge the quality of their books by their popularity. After all, if the purpose of reading is to deliver pleasure, then surely bestsellers are the ones who serve this purpose best. What this ignores, of course, is the quality of the experience. It is important not to confuse entertainment with joy. There may be people for whom reading Dan Brown or Chetan Bhagat is a revelatory and transformative experience, who step away from these authors with their minds alight and their senses on fire. Good for them. But for most people, I suspect, reading these authors is no less or more enjoyable than watching a sitcom on TV or gossiping with their colleagues over lunch. And the point is that reading is capable of delivering so much more. If you've never finished a book and come away with the sense (however fleeting) that the world is different, then you've never truly read a book. And believe me, you're missing out.

In any case, pragmatic considerations are hardly the strong suit of A Reader on Reading. If you're going to try and convert people who don't read seriously or see reading as trivial, writing a book that celebrates Dante, Homer, Borges and Cervantes is hardly the right way to go about it. Nor is extolling the civic importance of reading, which only serves to convert what is a privilege into a duty, what is an indulgence into a chore. I consider myself quite seriously committed to reading, but by the end of Manguel's umpteenth sermon about why reading matters even I was starting to chafe at the bit. There is much to delight in in Manguel's book, but it is a book meant for preaching to the choir, a set of essays by a quintessential book lover that only other book lovers will truly appreciate. Which is why it's frustrating that Manguel, who is clearly passionate about books himself (the man finds solace in a hospital bed re-reading Don Quixote!), confines himself to these dry abstractions in defense of reading, never explicitly acknowledging its more visceral delights.

Notes

[1] The man spent his early years hanging out with Borges! Color me bright green with envy.

[2] Manguel doesn't explicitly spell this out, of course, it's my reading of what he's saying, though I think it's a fairly accurate one. In any case, as Manguel himself would argue, a book is what the reader interprets it to be.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)