Wandering through the Philadelphia Art Museum's exhibition of the paintings of Frida Kahlo last Thursday, I couldn't help think of the similarities between Kahlo's work and Courbet's. Both are artists deeply invested in their self-image, to the point where their work, were it not for its brilliance, would seem like egoism. Both are concerned with being unconventional, and with shaking up their respective establishments. Both are passionately fond of the landscapes they grew up in, and delight in using these scenes as a setting for their work. And both are interested, in their own ways, in depictions of the female form; in redefining female beauty, portraying it in terms that are less pristine and therefore less feigned.

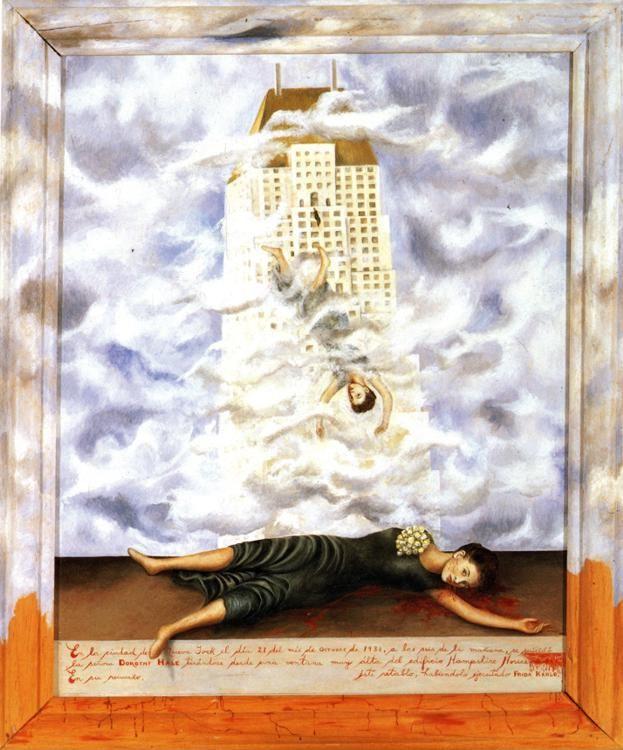

You have only to look at a Kahlo portrait (like the one above) though, to see where the comparison breaks down. For where Courbet's paintings radiate a sort of lazy, unconscious sensuality, his subjects often portrayed asleep or resting, Kahlo's dominant mode is confrontation. In painting after painting, the people in Kahlo's paintings stare back at you with a directness that seems almost a challenge. Kahlo forces us to pay attention to her images by having them pay attention to us - her paintings do not so much invite our gaze as demand it. In the dozen or so self-portraits that are included in the exhibition what you sense is not so much exhibitionism but a kind of generalized narcissism - this is a woman who is in love with the idea of looking directly at the world and having it stare right back [1]. And it's not only in the self-portraits that you feel this - nowhere is this sense of engagement more pronounced than in Kahlo's glorious portrayal of the Suicide of Dorothy Hale (below) in which the still open eyes of the corpse in the foreground glare back at you, their expression trapped somewhere between appeal and accusation, concentrated into an intensity that seems to deny Death itself.

Not that the expressions on her subject's faces is the only thing confrontational about Kahlo. The unflinchingness of her vision informs the content of what she paints: whether it's her

famous depiction of a miscarriage in Henry Ford Hospital - a woman (Kahlo) marooned on a blood soaked bed in the middle of a barren plain, surrounded by a surrealist constellation of images, the ribbons of blood connecting them to her womb turning the whole scene into a grotesque May pole dance - or the almost bathetically macabre A Few Small Nips with its bloodbath spilling onto the frame, Kahlo seems determined to embrace all that is visceral and cathartic in the human experience. What shocks about these paintings is not just the subjects they depict, but the fact that Kahlo is willing to inflict such violence on the female body (and by association, on herself) while continuing to identify with it - her refusal to distance herself from the victim, from the pain. To see the savage dislocation of Kahlo's heart in the Two Fridas, or the ruined spectacle of Kahlo's body in The Broken Column (below) is to witness a kind of divine masochism, a strip-mining of the self in the service of art that is as disturbing as it is courageous. R.S. Thomas speaks of an "impulse to conceal your wounds / from her and from a bold public / given to pry" - Kahlo it seems, has no such impulse, and it is this, coupled with the sureness of her visual instinct, that makes her unforgettable.

famous depiction of a miscarriage in Henry Ford Hospital - a woman (Kahlo) marooned on a blood soaked bed in the middle of a barren plain, surrounded by a surrealist constellation of images, the ribbons of blood connecting them to her womb turning the whole scene into a grotesque May pole dance - or the almost bathetically macabre A Few Small Nips with its bloodbath spilling onto the frame, Kahlo seems determined to embrace all that is visceral and cathartic in the human experience. What shocks about these paintings is not just the subjects they depict, but the fact that Kahlo is willing to inflict such violence on the female body (and by association, on herself) while continuing to identify with it - her refusal to distance herself from the victim, from the pain. To see the savage dislocation of Kahlo's heart in the Two Fridas, or the ruined spectacle of Kahlo's body in The Broken Column (below) is to witness a kind of divine masochism, a strip-mining of the self in the service of art that is as disturbing as it is courageous. R.S. Thomas speaks of an "impulse to conceal your wounds / from her and from a bold public / given to pry" - Kahlo it seems, has no such impulse, and it is this, coupled with the sureness of her visual instinct, that makes her unforgettable.

For all the virtues of Kahlo's more passionate work, though, the paintings I prefer are the ones where intensity is balanced with restraint, so that the work, without losing its focus on the themes of death and suffering, depicts these in subtler ways, juxtaposing the stately with the macabre, and producing images that are the more shocking for the contrast. Two Fridas is a good example of this, the figures themselves seem composed, almost preternaturally so, suggesting nothing so much as a traditional portrait of two sisters sitting side by side, so that the effect of the heart torn out from one's chest is amplified. Girl with a Death Mask has a similar effect - the promised innocence of the little girl's figure, daintily clutching a flower in it hand is shockingly belied by the skull of the face. Most shocking of all, though, in its repressed, almost invisible horror, is The Deceased Dimas Rosas Aged Three (below). The image by itself suggests no violence - the central figure seems content and king-like, with its tinsel crown, its scepter like flower, its satisfied, almost complacent expression. It takes a moment for reality to seep in - what you are looking at is not some smug regent but the corpse of a three year old child, complete with poignant little toes pointing into the air and a circle of plucked flowers, the single note of outrage in the whole scene a black and white image of a Christ-like figure tied to a post placed on the pillow by the girl's head.

The Philadelphia Art Museum exhibition is a splendid collection of Kahlo's work, including many of her finest and most famous paintings, covering the full range of her work from the

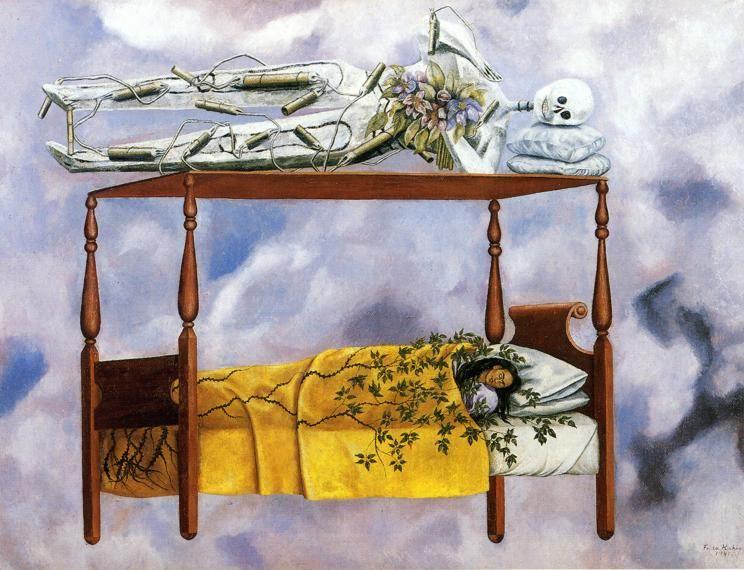

baroque, intricately programmatic visions of Moses and My Dress Hangs There (right) to her still life of Pitahayas, and showcasing many of Kahlo's abiding themes - the emphasis on linkages and bloodlines (most vividly seen, perhaps, in Family Tree), the repeated motif of exposed roots. Much of what I saw was familiar (though it's always a treat to see paintings like Dream - left - and

baroque, intricately programmatic visions of Moses and My Dress Hangs There (right) to her still life of Pitahayas, and showcasing many of Kahlo's abiding themes - the emphasis on linkages and bloodlines (most vividly seen, perhaps, in Family Tree), the repeated motif of exposed roots. Much of what I saw was familiar (though it's always a treat to see paintings like Dream - left - and  the Love Embrace of the Universe in the original - since reproductions simply don't do them justice), but I also made a number of new discoveries, including the anthropomorphic The Flower of Life (below) and a hauntically delicate portrait of a young girl placed between the sun and the moon (which I can't seem to find online).

the Love Embrace of the Universe in the original - since reproductions simply don't do them justice), but I also made a number of new discoveries, including the anthropomorphic The Flower of Life (below) and a hauntically delicate portrait of a young girl placed between the sun and the moon (which I can't seem to find online). That painting, though painted later, seems like a premonition of what is, perhaps, Kahlo's most indelible self-portrait, and the painting that best sums up her work. In Self-Portrait on the Border between Mexico and the United States (below) Kahlo stands on the margin of two worlds - the land of primal gods and ruined dreams and the land of modernism with its robot-like pipe figures, its electrical vegetation and concrete towers. Placed between these two landscapes, Kahlo herself seems an enigmatic and contradictory figure, the pink ruffled dress and elbow length gloves at odds with the revolutionary air of the casually held cigarette and the Mexican flag - as though she had been dragged away from a party to face, coolly, a firing squad. Seen three quarters of a century after it was painted it is the portrait of an iconoclast, a female colossus, who stands on the border not between Mexico and the United States but between the past and the future, myth and reality. And it is emblematic of everything Kahlo has come to mean, that her expression as she stands there is one of fierce certainty, eyebrows arched, mouth set in hard, proud line, lucid eyes staring right back at you.

That painting, though painted later, seems like a premonition of what is, perhaps, Kahlo's most indelible self-portrait, and the painting that best sums up her work. In Self-Portrait on the Border between Mexico and the United States (below) Kahlo stands on the margin of two worlds - the land of primal gods and ruined dreams and the land of modernism with its robot-like pipe figures, its electrical vegetation and concrete towers. Placed between these two landscapes, Kahlo herself seems an enigmatic and contradictory figure, the pink ruffled dress and elbow length gloves at odds with the revolutionary air of the casually held cigarette and the Mexican flag - as though she had been dragged away from a party to face, coolly, a firing squad. Seen three quarters of a century after it was painted it is the portrait of an iconoclast, a female colossus, who stands on the border not between Mexico and the United States but between the past and the future, myth and reality. And it is emblematic of everything Kahlo has come to mean, that her expression as she stands there is one of fierce certainty, eyebrows arched, mouth set in hard, proud line, lucid eyes staring right back at you.

[1] I am reminded of a line from Berryman - "He stared at ruin. Ruin stared straight back."

4 comments:

Coincidentally, 3quarksdaily has a poem today about Frida Kahlo's eyebrows.

OT: You might feel deeply enough about this to want to blog it.

[Via]

Not that I don't envy you all the museums and the paintings and oh, yes, the Wajda...

i don't know much about art,but the pictures represent the highest expressions in the most insane sanity form..

Not a peep from you for too long now. Where are you?!

Post a Comment