Goya's Ghosts

[spoiler alert]

What in God's name has happened to Milos Forman? His latest film, Goya's Ghosts, looks like the work of someone who's been locked up in a dark dungeon for so long that he's no longer capable of coherent thought and wanders through the streets of his period drama set muttering to himself. Forget the Spanish Inquisition - the real torture here is having to sit through the appalling two hours of this film. If John Madden had made this film, it would be a disappointment; coming from Forman (and with Jean-Claude Carriere and Javier Bardem throwing in their talents) it feels like a betrayal.

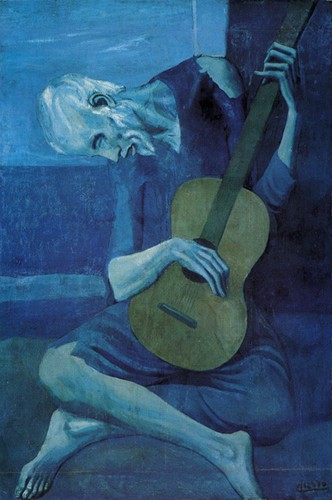

The movie opens with a shot of the monks of the Spanish Inquisition passing around a booklet of Goya's etchings [1]. Ah ha! you think - you see it all now. Great artist tortured for his work by fanatical zealots, history having the last laugh, that sort of thing. But no, five minutes into the film the monks have decided Goya is too well-connected to go after. Exit Goya (oh, he'll keep turning up every now and then, like a bad Real, but at this point most of the film's focus on his work is already over). Enter instead Ines Bilbatua (Natalie Portman) whom the Inquisitors decide to pick on instead, presumably on the theory that if you are going to hang someone naked from the ceiling it may as well be someone people will pay money to see in the buff. The charge against Ines, it turns out, is not that her accent keeps wandering all over the place (thus proving her the spawn of the devil) but that she won't eat her greens...errr...pork, thus proving that she secretly practices Jewish rites. Poor, sweet, innocent Ines is gruesomely tortured until she confesses to her heresy (shouting "Tell me what the truth is" when asked to confess it) and locked away, still naked, in a dungeon.

The politics of this is so ham-handedly obvious that the message would be self-evident to a five year old child (not that this is an appropriate film for five year olds to watch) but just in case you were too busy snarfing your popcorn to get it, Forman then proceeds, in a (literally) tortuous twenty minute scene showing the Inquisitor Brother Lorenzo's (Javier Bardem) visit to Ines' family, to spell it out for you. Here the whole 'confession under torture being meaningless' theme is discussed in a stilted dinner conversation, after which Ines' family, in a show of true Spanish hospitality, proceed to torture their dinner guest until he confesses to being a monkey.

In an article in the New Yorker about the film, Forman claims that audiences in Spain who watched the film burst out in applause over this scene. Personally, I found it horrifyingly bad. It's not just that it makes no sense from the perspective of the plot (your daughter's being held by the Spanish Inquisition - what do you do? - you invite the Grand Inquisitor over for a meal, torture him till he confesses to being an ape and - this is the worst bit - get away with it; why didn't they put him in the comfy chair while they were at it?), or that it comes off as being totally artificial (and to think this is the man who once made Fireman's Ball) it's also that it undermines, for me, the political message. Being opposed to torture means condemning it in all circumstances, not fighting it with tortures of your own.

At any rate, Brother Lorenzo is soon disgraced and disappears, leaving behind a portrait of him by Goya that will be burnt in the public square and a pregnant Ines, whom Lorenzo has forced himself on in the name of 'praying with her', but whom he now deserts in prison, proving yet again that workplace romances don't last.

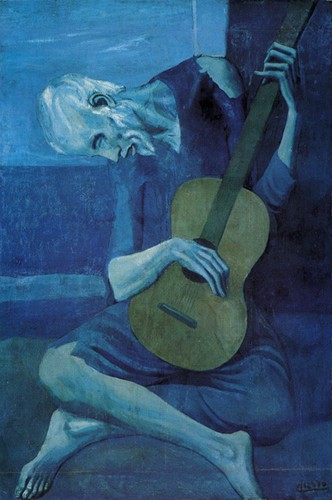

And if you thought Part One was bad, Part Two is infinitely worse. The scene opens fifteen years later. Goya is now completely deaf (a condition signaled in part one by the onset of a sudden ringing, which left him clutching his ears like someone with a bluetooth and a particularly annoying ring tone) which means he (mercifully) can't hear himself ramble through a long monologue about the devastation wrought on Spain by the French, which he, Goya, is chronicling with his work [2]. The coming of the French means that all prisoners of the Spanish Inquisition are released, including Ines, who emerges looking suitably hag-like, her fifteen years in prison having reduced her to a lifetime of borderline sanity, uncombed hair and bad make-up. She makes her wandering way home, only to find that her family, having waited for her for fifteen years, have been conveniently killed just a few hours before, their corpses laid out artistically on the steps for her to find. A special prosecutor from Emperor Napoleon arrives to look into the excesses of the Inquisition, and who should it turn out to be but good old Brother Lorenzo, now a happily married Voltaire-worshipper. Ines has lost her daughter, but Goya helpfully spots her in the park - a task made easy by the fact that this daughter, named Alicia, is also played by Ms. Portman, in the kind of double role one had hoped had died out with Hema Malini films. Coincidence piles on coincidence, a lot of people make a lot of fiery but didactic speeches, political fortunes rise and fall making a point about the fleetingness of power with schoolboy earnestness, but the whole thing adds up to little more than a piece of dramatic fluff.

The worst thing about the film is the way its invocation of Goya turns out to be a complete red herring. Oh, he's around all right, and ties the plot together, but he's less the tortured painter we know and love, and more a benign godfatherly figure who wanders around trying to help people. He could be Goya the Good Doctor, or Francisco the Gentle Merchant, or Cutts the Polite Butcher for all the movie tells us. There are certainly a few scenes early on that show the master at work (including one particularly lovely sequence detailing the process by which an etching is made) and time and time again an image in the film will echo a Goya painting, but the overall effect is soulless and empty, and the way Goya is reduced to playing a weak supporting role is deeply annoying. Imagine a version of Amadeus where the real story was the descent of Salieri's love child into prostitution, and Mozart just popped up now and then as that guy working at his desk until the girl knocked on his door.

The closest this movie gets to actually investigating Goya's art is a scene where he presents a portrait of the Queen of Spain that shows her as the aging, somewhat plain woman she truly is. The Queen, not evidently a great admirer of realism, is miffed by this, and Goya finds himself tete-a-tete with the King (played in a terrible false note by Randy Quaid) and is on the verge of a discussion about his art when a messenger breaks in to announce that the French Revolution has taken place and Louis XVI has been executed (yes, the film really is that phony). And that's it. We get a couple of other throwaway speeches about the meaning of Art, a frenzied claim by Goya that Ines is his muse (a fact we're shown almost no evidence of) and one depressingly fake shot of Bonaparte's brother picking out paintings from the National Gallery (he likes Velazquez but doesn't care for Bosch) to send to France, but the film never really manages to engage with Goya's art in any meaningful way.

Overall, Goya's Ghosts is an infuriatingly bad movie, one that you absolutely should not watch, not even out of a sense of misplaced loyalty to Forman (as I did). The kindest thing we can do for Forman now may be to forget that he ever made this film.

[1] I'm not an art historian, and I saw little more than glimpses of the etchings they were passing around, but I'm not sure about the historical accuracy of this. According to the movie, these etchings were in wide circulation in 1788, whereas Capprichos, the collection I thought those etchings were taken from didn't come out till 1799. Anyone know if Goya actually had a book of etchings out in 1788?

[2] Forman's idea throughout the film seems to be that rather than bothering to show something happening (and letting the audience interpret it) you should just add on an artificial speech where one of the characters self-consciously spells out your message, rather like a narrator in a primary school play.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Twitter

Posts

Posts

Posts

Posts

Of shoes -- and ships -- and sealing wax -- Of cabbages -- and kings -- And why the sea is boiling hot -- And whether pigs have wings.

About Me

- Falstaff

- Minneapolis, MN

- GB$(GL) d- s+:++ a C W+(++) w PS++ PE--(++) !tv b++++ DI++++ m++++ e++++ h+ r* z-->---

Blog Archive

-

▼

2007

(290)

-

▼

July

(23)

- Guitar Notes

- They're dropping like flies now

- Ingmar Bergman (1918-2007)

- Hourglass

- Paraphernalegia

- The Match Girl

- The Mighty Fallen

- Tut! Tut!

- Harry Potter and the Deathly Halitosis

- Carson and Harms

- Not in our stars

- Stoning the Romances

- Romancing while stoned

- To see the world in a cup of coffee

- Take One

- Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves

- I dreamt you died

- Trains, planes, buses and Ambassadors

- Meanwhile, Billy Strayhorn is taking the swan into...

- Cooking, with Gusteau

- I spam what I am

- Oregon Trails - Part 2

- Oregon Trails - Part 1

-

▼

July

(23)

Recent Comments

Method to the Madness

Subscribe To

Site Meter

StatCounter

E-mail:

specktre@gmail.com

3 comments:

Since there was no particular accent used by anyone in the film with the exception of Bardem who can't quite get rid of his spanish accent, why pick on Natalie Portman by stating the her accent was wandering all over the place. I thought she was quite good in the two roles that she played and that your review of this film was very, very crappy - point of fact, what have you produced or directed lately? The film was filmed beautifully and, thank God, it was done in such a manner that one could detach and pay attention without getting all sentimental and boo-hoo about what was going on because this was not another Hostel or Saw 1 thur VI but about an actual bloody time in the his Spanish history. Though it was a work of fiction, I am very glad someone had the gumption to do a film on this period as no one has ever done one before.

In answer to this comment by the reviewer:

"Forman's idea throughout the film seems to be that rather than bothering to show something happening (and letting the audience interpret it) you should just add on an artificial speech where one of the characters self-consciously spells out your message, rather like a narrator in a primary school play."

Did you ever watch Deadwood on HBO? Any episode or scene? It was full of foulmouthed but poetic Shakespearean style monologues which commented precisely on what was going on. I lived to hear and see the actors perform on that show every week. Besides putting Ian MacShane on the map, it introduced us to the wonderful and pithy William Sanderson, a little known character actor until then, best known for playing one of three idiot brothers on the old Newhart show. Additionally, likening the dialogue to that of a primary school play makes me wonder if the reviewer ever got beyond primary school, because he didn't understand the film.

Again I must dispute another of the reviewer's comments:

"I'm not an art historian, and I saw little more than glimpses of the etchings they were passing around, but I'm not sure about the historical accuracy of this. According to the movie, these etchings were in wide circulation in 1788, whereas Capprichos, the collection I thought those etchings were taken from didn't come out till 1799. Anyone know if Goya actually had a book of etchings out in 1788?"

The etchings were indeed from 1799, however, as this was a work of fiction, a little poetic license must be allowed as the etchings were meant to represent the grotesque vileness of the times that the film was depicting. The reviewer probably would not find anything amiss with "Gone With the Wind", however, there were many mistatements of historical fact both in the book and the film. I don't believe Ines Bilbatua and Lorenzo Casares were real characters, but were actually fictional, so why split hairs over historical time lines. The drawings were not made public until 1799, but were drawn to represent or during an earlier time.

Post a Comment