"The landlady says he lived here

"The landlady says he lived herefor years. There's enough missing

for me to know him. On the empty shelves,

absent books gather dust"

- Agha Shahid Ali, 'The Previous Occupant'

A pair of boots lying stranded in the sand, a scratched door, a place laid at the table, the track of a heron at the water's edge, an empty hanger. Life, in Andrew Wyeth's paintings, exists at a remove, visible not so much in itself as in the impression it leaves on things around it. There are no people in these paintings, there is only the lingering aura of their presence - the canvas is still warm with it [1] . Life, it seems, was here a minute ago, has just stepped out for a minute, may or may not be back. It's Wyeth's ability to paint landscapes that are not so much empty as vacated, deserted, that is, in my view, his true gift.

But objects, in Wyeth are not simply clues to an absence. They are also stand-ins for people, metaphors for the states of mind of that inhabit these paintings like nostalgic ghosts. Thus the

dominating presence of a father becomes a hill that blots out almost all the horizon, shrinking to a sepulcharal rock only after his death;

dominating presence of a father becomes a hill that blots out almost all the horizon, shrinking to a sepulcharal rock only after his death;  an exquisite pairing of doors (and buckets) becomes the memory of beloved couple; a drowned girl is transformed into a web of nets trailing in the wind;

an exquisite pairing of doors (and buckets) becomes the memory of beloved couple; a drowned girl is transformed into a web of nets trailing in the wind;  a pair of coats hanging by a window become symbols of a man's beliefs; a locked, stifling window is isolation, a window thrown open with the breeze blowing into it is new hope. Again and again, with an imagination and

a pair of coats hanging by a window become symbols of a man's beliefs; a locked, stifling window is isolation, a window thrown open with the breeze blowing into it is new hope. Again and again, with an imagination and accuracy that Ovid would have been proud of, Wyeth transforms everyday scenes and objects into metaphors of our deepest, most fragile feelings, so that to spend an hour staring at his paintings is to come away with a profound belief in the sympathy of the inanimate, in the way that shapes and objects share in the turmoil and suffering of our hearts.

accuracy that Ovid would have been proud of, Wyeth transforms everyday scenes and objects into metaphors of our deepest, most fragile feelings, so that to spend an hour staring at his paintings is to come away with a profound belief in the sympathy of the inanimate, in the way that shapes and objects share in the turmoil and suffering of our hearts.

What is notable about these paintings is the way the present has almost entirely leached out of them. It's as though Wyeth, with his painstaking use of tempera, is trying to stick the layers of time back on. These paintings date from the last half century, yet there is hardly any mention of the modern world in them (cars appear twice, an aeroplane once). In an age when most of his contemporaries were experimenting with a multitude of new forms, colours and styles in an attempt to give expression to the changing world, Wyeth's hermetic, pristine work seems part timeless, part anachronistic. Seeing Wyeth's paintings is like reading Frost, a feeling of intense beauty, with just the sense, at the back of your mind, of being out of tune with the age. This then is the greatest of all Wyeth's absences - he hasn't just painted the people out of his landscapes, he has left out the Present, the World - he has left out Time itself.

It is, of course, dangerous to stereotype. If there is one thing that astonishes about Wyeth, it is the range that his work covers - from watercolours reminiscent of Winslow Homer;

to thick nature paintings that bare traces of Gauguin; to Hopper like buildings;

to thick nature paintings that bare traces of Gauguin; to Hopper like buildings;  to a series of interiors that remind one, in their use of light, of Vermeer; to some intense, unforgettable portraits.

to a series of interiors that remind one, in their use of light, of Vermeer; to some intense, unforgettable portraits.

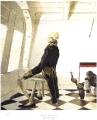

There is also Wyeth the surrealist, who appears in such paintings as Embers (a dying fire, the place of the embers taken up by lobster shells), Dr Syn (a skeleton in pirate costume seated at a window, a cannon placed behind him, looking out to sea), Christmas Morning (a stunning painting of a dying man sitting up in bed,

There is also Wyeth the surrealist, who appears in such paintings as Embers (a dying fire, the place of the embers taken up by lobster shells), Dr Syn (a skeleton in pirate costume seated at a window, a cannon placed behind him, looking out to sea), Christmas Morning (a stunning painting of a dying man sitting up in bed, staring down a moonlit path that meanders to where a ghostly new star gleams in the sky) and a painting of two hands rising out of the snow whose title I can't remember now. And there is Wyeth the master of perspective, seen most vividly, perhaps, in Soaring.

staring down a moonlit path that meanders to where a ghostly new star gleams in the sky) and a painting of two hands rising out of the snow whose title I can't remember now. And there is Wyeth the master of perspective, seen most vividly, perhaps, in Soaring.

And finally, of course, there are the off-beat little gems: a gloriously dark portrait of a black man sitting by himself in an armchair (Monologue); a painting of a young girl and her dog lying in the grass (Distant Thunder), a brutal, almost Munch like vision of Wolf Hill.

And finally, of course, there are the off-beat little gems: a gloriously dark portrait of a black man sitting by himself in an armchair (Monologue); a painting of a young girl and her dog lying in the grass (Distant Thunder), a brutal, almost Munch like vision of Wolf Hill.Make no mistake - Wyeth is not one of the great artistic innovators of the century - his vision is nostalgic, almost retrogressive - the real action is elsewhere. But it is precisely the absence of action, the contingent beauty of the natural world just before art happens to it, that Wyeth captures perfectly. He is not one of the immortals (he is, in fact, acutely aware of his own mortality) but he is sad and sublime and timeless. If there is always something missing in his work, it is because he has chosen to leave it out.

[1] This incidentally is something the exhibition showcases - one gallery traces the development of two of Wyeth's paintings, showing you how Wyeth, in his initial studies, includes people in the paintings, only leaving them out when it comes to the final work.

Categories: Arts

8 comments:

you gave us lot of insight into wyeth's art.the photos of the paintings are too good...its as if i myself is in that art gallery gazing at the paintings.

are the pictures downloaded from net or u've taken them from your cell?

cool post.

Thanks for the fantastic write up.

Hmmm..personally I see a lot of movement in these paintings..like they are there for some action to happen. "A pair of boots lying stranded in the sand" almost foretells an event, that is waiting to occur.

I loved your take on these objects as "metaphors", but Wyeth being the hardcore realist that he is, would he turn his painting into an analogy?

On a tangent as usual, but would you call cinema an art form, or as Ray says in one of his essays, ('Chalachitra Rachona: Aangik, Bhasha O Bhongee', Chalachitra, Annual Issue, 1959)a 'language'?

"...Image and sound. An image here is not just a picture. It is a picture that speaks. In other words, the picture does not begin and end in itself, the way a painting does. What matters chiefly here is the meaning of the image. Every image is like a whole sentence, and the sum total of all the images is the final message of the film. Even in the silent era, images carried meanings. Their language was not dependent on dialogue."

rumple: Thanks. The pictures are all downloaded from the Net. As for the insight, well, much of it comes from descriptions that go with each painting.

Venkat: Thanks

k: right, but that's exactly what I'm saying is well - nothing is really happening, but lots of stuff is about to happen.

And I don't know about Wyeth as a hardcore realist. His images are drawn from real life, true, but that doesn't mean they don't speak to things beyond the immediately visible. In general, I don't know that realism and analogy can't go hand in hand. Think about Chekhov - is the great plain whose crossing Chekhov so lovingly describes really just a plain. Or is it a metaphor for something else?

d&c: some tangent. I would say both - I don't see why it has to be one or the other. After all, art is only, in some sense, the bringing of language to perfection; if cinema is a language than Ray's films, and Kurosawa's, are its finest poetry.

Nice descriptions. Cheesy comparison, but the whole portraits of absence, empty stages without the actors etc. reminds me of a Stephen King short story, 'The Langoliers', where a group of flight passengers find themselves trapped in a world that lags the present time by a few seconds. The world is intact but unpopulated, since the people occupying it have moved on.

Wonderful and informative web site. I used information from that site its great. Health insurance for farm families 1969 oldsmobile cutlass 442 zithromax bei schlangen 63 oldsmobile f85 Parts 1976 oldsmobile regency 98

Enjoyed a lot! scanners barcode Phentermine with no rx required

Post a Comment