Beauford Delaney: The Colours of Jazz

Whenever you see colour, think of Beauford Delaney. Delaney's pallete is vibrant and masterful - his paintings literally seethe with colour - vivid reds and passionate yellows run like worms within the living clay of his art. The current exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum showcases Delaney's evolution as an artist, from a loving chronicler of the explosive energy of New York in the 1940s to the purer abstraction of his Paris years. The difference between the two is stark - the early paintings are blurred negatives of plastic colour, pulsing landscapes of a city that capture almost perfectly the manic energy of New York. These paintings start with a vision of urban beauty that owes much to the Ashcan school and the aching peoplescapes of Hopper and others, except that where these painters are muted and sombre, Delaney is vivacious and daring - combining these visions of his beloved city with a range of colouring that owes more to Van Gogh and Matisse than to any of his contemporaries. Highlights for me from this part of the exhibition were a painting for Marianne Robinson as well as a series

Whenever you see colour, think of Beauford Delaney. Delaney's pallete is vibrant and masterful - his paintings literally seethe with colour - vivid reds and passionate yellows run like worms within the living clay of his art. The current exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum showcases Delaney's evolution as an artist, from a loving chronicler of the explosive energy of New York in the 1940s to the purer abstraction of his Paris years. The difference between the two is stark - the early paintings are blurred negatives of plastic colour, pulsing landscapes of a city that capture almost perfectly the manic energy of New York. These paintings start with a vision of urban beauty that owes much to the Ashcan school and the aching peoplescapes of Hopper and others, except that where these painters are muted and sombre, Delaney is vivacious and daring - combining these visions of his beloved city with a range of colouring that owes more to Van Gogh and Matisse than to any of his contemporaries. Highlights for me from this part of the exhibition were a painting for Marianne Robinson as well as a series

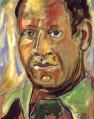

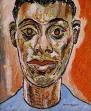

of portraits of James Baldwin that highlight Delaney's versatility - ranging from a simple pastel sketch of a young open-faced Baldwin, through a gloriously god-like portrait of Baldwin as Dark Rapture and a intense, almost disturbingly close portrait of Baldwin done in darker tones, to a portrait of on older Baldwin as a black sage, an idol of dark and terrible gravity, a negative force on a background as red as blood.

of portraits of James Baldwin that highlight Delaney's versatility - ranging from a simple pastel sketch of a young open-faced Baldwin, through a gloriously god-like portrait of Baldwin as Dark Rapture and a intense, almost disturbingly close portrait of Baldwin done in darker tones, to a portrait of on older Baldwin as a black sage, an idol of dark and terrible gravity, a negative force on a background as red as blood.Where Delaney really comes into his own for me, though is in his later, Paris years. The paintings here are entirely abstract, yet staring at them one has the hypnotic sense of shape struggling to be born, of the imminence of pattern. At first glance, these paintings seem blank, evenly shaded - it's only when you look at them more closely that you begin to see the subtle dance of colour hidden away inside them, the clever little insinuations of light and dark that fall just short of becoming form. It's because of this that these paintings seem startlingly alive,

incredibly real. The overall effect is stunning - in a series of paintings titled simply Abstraction Delaney captures the essence of each season, contrasting the brooding maroon of autumn with the lighter, yellowish-green of spring. Also on display is his stunning tribute to Charlie Parker - a painting that is pure pulse - lines of electricity exploding out from the centre of the page.

incredibly real. The overall effect is stunning - in a series of paintings titled simply Abstraction Delaney captures the essence of each season, contrasting the brooding maroon of autumn with the lighter, yellowish-green of spring. Also on display is his stunning tribute to Charlie Parker - a painting that is pure pulse - lines of electricity exploding out from the centre of the page.The thing that connects these two very different phases of Delaney is colour. Whether his subject is an urban landscape or the pure abstractions of the mind, Delaney is an artist of furious and contagious hues - colour breaks out all over his paintings like a rash, like a disease. Throughout the exhibition there is a sense of passionate, almost greedy density, of paint scraped onto the canvas with a knife, of colour that is inches thick. There is something very solid and aggressive about Delaney's painting, something insistently opaque, and it is this that makes him the exciting painter he is.

I can't end this description without mentioning my favourite painting of the entire exhibition - a stunning portrait of Ella Fitzgerald - a background of abstract and living yellow from which a pair of eyes emerge, and a face like a half formed moon beams out onto the canvas. A painting that showcases, in a single work, both Delaney's mastery of portraiture as well as his command of vivid abstraction.

Jacob van Ruisdael: Master Dutchman

From the rebellious to the sublime. If Delaney's work dazzles you with energy, the exhibition next door, featuring the works of master landscape artist Jacob van Ruisdael, is a study in harmony and light, in the quiet perfection of the great Dutch masters. Ruisdael is one of the 17th century's most admired landscape artists, a painter whose work inspired, among others, the great John Constable (a fact that the current exhibition makes much of - showcasing works of Constable that are clearly inspired by the Dutch painter). His works are masterpieces of timeless grandeur, paintings of exquisite and epic balance.

From the rebellious to the sublime. If Delaney's work dazzles you with energy, the exhibition next door, featuring the works of master landscape artist Jacob van Ruisdael, is a study in harmony and light, in the quiet perfection of the great Dutch masters. Ruisdael is one of the 17th century's most admired landscape artists, a painter whose work inspired, among others, the great John Constable (a fact that the current exhibition makes much of - showcasing works of Constable that are clearly inspired by the Dutch painter). His works are masterpieces of timeless grandeur, paintings of exquisite and epic balance.

Ruisdael is the quintessential landscape painter. People are of little interest to him - indeed in most of his paintings the human and animal figures are added by other artists. What Ruisdael delights in is the sheer scale of the natural world -  the soaring majesty of trees, the sad beauty of ruined towers, the breathtaking power of distance. His paintings are studies in perspective, touched impeccably by light and instinctively highlighting the glory of a universe where man is purely incidental. To see a Ruisdael painting is to be transported into a world of dreamlike perfection, where even the raging torrent of a waterfall seems stilled, timeless.

the soaring majesty of trees, the sad beauty of ruined towers, the breathtaking power of distance. His paintings are studies in perspective, touched impeccably by light and instinctively highlighting the glory of a universe where man is purely incidental. To see a Ruisdael painting is to be transported into a world of dreamlike perfection, where even the raging torrent of a waterfall seems stilled, timeless.

The first thing you notice about Ruisdael's paintings is the sky. In painting after painting, the sky dominates the larger part of the canvas, a sky alive with majestic clouds, with shapes of unearthly power. There is an incredible depth to Ruisdael's work, his paintings seems to sweep away into the distance, the line of the land perfectly horizontal, betraying the full breadth of open space. Nowhere is this more evident than in this landscape of Ruisdael's native Haarlem, where the tiny rooftops of the town have been squeezed into the shadow of the church spire, leaving the horizon unbroken.

The second thing you notice about Ruisdael's paintings are the trees. Ruisdael's trees are more than just the big plants that make up a forest - each tree is a unique vision of beauty, a seething form of almost abstract energy, rising gloriously out of the earth, every leaf on its branches aflame with light. Again and again Ruisdael paints these mighty monarchs of the forest with a passion is almost nostalgia, until the trees in his painting have an electrifying, almost hypnotic quality - it is difficult to tear your eyes away from them to see anything else.

The second thing you notice about Ruisdael's paintings are the trees. Ruisdael's trees are more than just the big plants that make up a forest - each tree is a unique vision of beauty, a seething form of almost abstract energy, rising gloriously out of the earth, every leaf on its branches aflame with light. Again and again Ruisdael paints these mighty monarchs of the forest with a passion is almost nostalgia, until the trees in his painting have an electrifying, almost hypnotic quality - it is difficult to tear your eyes away from them to see anything else.

Yet if trees are symbols of the organic, chaotic quality of nature, ruins, in Ruisdael becomes pillars of light, razor-sharp evocations of lost glory.

Yet if trees are symbols of the organic, chaotic quality of nature, ruins, in Ruisdael becomes pillars of light, razor-sharp evocations of lost glory.  Remember the line about sunlight on a broken column. Again and again, Ruisdael returns to this vision of beauty, using the debris of history to construct images of desperate melancholy of aching and absolute longing. Light in these paintings (which are my favourite in the exhibition, and include some stunning landscapes of Edmonton castle, as well as a justly acclaimed painting of a Jewish cemetery) is an act of benediction, a form of grace.

Remember the line about sunlight on a broken column. Again and again, Ruisdael returns to this vision of beauty, using the debris of history to construct images of desperate melancholy of aching and absolute longing. Light in these paintings (which are my favourite in the exhibition, and include some stunning landscapes of Edmonton castle, as well as a justly acclaimed painting of a Jewish cemetery) is an act of benediction, a form of grace.

In the final analysis, Ruisdael's paintings are the landscapes of fantasy, perspectives from a world of uncompromising perfection, the kind of world that God would have created before he let humans in. Human presence is never wholly absent from these paintings, but for the most part it is there only to be dwarfed, only to be shown to be irrelevant. Sunlight and forests and clouds are the true heroes of Ruisdael's world, and it is these that he is most interested in painting.

In the final analysis, Ruisdael's paintings are the landscapes of fantasy, perspectives from a world of uncompromising perfection, the kind of world that God would have created before he let humans in. Human presence is never wholly absent from these paintings, but for the most part it is there only to be dwarfed, only to be shown to be irrelevant. Sunlight and forests and clouds are the true heroes of Ruisdael's world, and it is these that he is most interested in painting.

The final set of paintings in the exhibition is a fascinating series of late seascapes. Here again, we see the characteristic Ruisdael touch - a tiny sale of glorious white catches our attention, drawn into the painting by it, we observe the incredible distance that the canvas stretches to, the calm of the horizon contrasting so vividly with the churning sea closer at hand. I am reminded, inevitably of Manet.

Taken together, Ruisdael's work has the awe-inspiring feel of a revelation; I walk out of the exhibition hall feeling as though I were walking out of a church.

1 comment:

Did they showcase Ruisdael's etchings? He was brilliant at that too. I like his obsession with trees. They are personalities in themselves and literally take over the canvas.

Post a Comment